All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

New Insights into the Mechanisms of Innate Immune Receptor Signalling in Fibrosis

Abstract

Recent advances in our understanding of innate immunity and inflammation have direct bearing on how we understand autoimmunity, and fibrosis, and how innate immune sensors might stimulate both of these key features of several fibrotic diseases. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the major receptors for recognizing pathogen associated molecular patterns present on bacterial cell walls, such as LPS, and nucleic acids (RNA and DNA). Several intracellular pathways mediate TLR effects and initiate various pro-inflammatory programs. Mechanisms for control of inflammation, matrix remodeling, and ultimately fibrosis are also activated. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), Interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-13 (IL-13), and interferon (IFNs) appear particularly important in regulating pro-fibrotic aspects of innate immune activation. These mechanisms appear important in fibrotic disease affecting multiple organ-systems, including lung, liver, kidney, and skin. These observations provide new paradigms for understanding the relationship between immunity/inflammation and fibrosis, however, the precise ligand and mechanism linking innate immune sensor(s) to fibrosis remain uncertain in most illnesses.

INTRODUCTION

Fibrosis is the end result of many inflammatory illnesses and despite its utility in repairing damaged tissue often leads to organ dysfunction, in many diseases becoming the main pathologic cause of organ dysfunction. Pathways for initiating inflammation include an expanding number of different sensors, including the family of toll-like receptors (TLRs), non-TLR nucleic acid receptors, the inflammasome, and scavenger receptors [1]. At the same time these receptors activate various pro-inflammatory pathways, mechanisms for control of inflammation, matrix remodeling and ultimately fibrosis are also activated. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), Interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-13 (IL-13) and interferon (IFNs) appear particularly important in mediating pro-fibrotic aspects of innate immune activation. Our understanding of these processes in vivo has typically been examined in affected end-organs, revealing common themes but also specific features of inflammation in different organs. However, the precise ligand and mechanism linking innate immune sensor(s) to fibrosis remain uncertain in most illnesses.

INNATE IMMUNE RECEPTORS

Toll-Like Receptors

TLRs are the major receptors for recognizing pathogen associated molecular patterns present on bacterial cell walls, such as lipopolysaccaride (LPS, TLR4 ligand) and nucleic acids (RNA and DNA, TLR3 and TLR7, and TLR9 ligands, respectively). Several intracellular pathways mediate TLR effects, most importantly Myd88, which is activated by all TLRs except TLR3, and TRIF/TICAM, which is activated selectively by TLR3 and also by TLR4 ligands. Myd88 sequentially activates IRAK4, TRAF6, TAK1, and NF-kB and MAP kinases, upregulating inflammatory cytokines and interferons (IFNs). TRIF/TICAM sequentially activates TBK and IRF3, upregulating IFNβ. TLRs and their effects are also dependent on the cellular distribution of TLRs within a given cell type and tissue. In addition to these inflammatory mediators, a growing literature implicates TLR activation in tissue remodeling and fibrosis. Whether profibrotic effects of TLR activation are direct or indirect, and the intracellular pathways and cytokines mediating these effects remain uncertain.

NON-TLR NUCLEIC ACID RECEPTORS

Cytoplasmic Nucleic Acid Receptors

Over the past several years a variety of non-TLR innate immune receptors have been identified. One class of innate immune sensors are the RNA helicases: retinoid acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), melanoma differentiation-associated gene-5 MDA5) and LGP2, RIG-1 and MDA5 containing caspase recruitment domains (CARDs), These RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) sense cytoplasmic double-stranded RNA with binding and downstream activation of IFNβ, thus sharing these features with the endosomal dsRNA sensor, TLR3 [2, 3]. However, intracellular signaling is mediated by interaction with CARD domains of IPS1/MAVS, which aggregate IPS1/MAVS, activating IRF3 and NF-kB through IKK and TBK1, respectively [4]. In addition to activating IFNβ, RIG-I activates MAV-independent stimulation of inflammatory cytokines through a pathway requiring CARD9, and inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion through a pathway requiring caspase-1 [5].

Another group of innate immune receptors recognizing cytosolic DNA are the PYHIN family of DNA receptors. AIM2, the best studied, activates the inflammasome through ASC [6], the same adapter used by NALP members of the NOD-like family receptors (discussed below). Thus, AIM2 provides another link for nucleic acid stimulation of IL-1β secretion.

DAI/ZBP1 (DNA-dependent activator of IRFs/Z-DNA binding protein 1) is another cytoplasmic DNA receptor [7]. However, it shares downstream signaling with the RIG-I receptors activating NF-KB through STING and then RIP1/RIP3.

NOD-Like Receptors and the Inflammasome

TLR-independent innate immune sensors also include NOD-like receptors (NLRs). NOD1 and NOD2 members of this family recognize bacterial peptidoglycan fragments [8], mediating downstream signals that activate NF-kB through CARD domains, whereas NALP family members, such as NALP1/NALP3, stimulate assembly of the inflammasome, a complex that includes ASC, recruiting capase-1, which cleaves and activates pro-IL-1beta and pro-IL-18. As discussed below, IL-1beta has been associated with inflammation and fibrosis in several animal models. There are 14 NALP family members directly or indirectly recognizing a wide range of molecular patterns from uric acid to nucleic acids to ATP. Inflammasome- and TLR-mediated signals provide complementary activities with TLR agonists stimulating pro-IL-1β production and caspase-1 converting it to its active form [9].

SCAVENGER RECEPTORS

Scavenger receptors on macrophages may also play roles in innate immune responses. CD163 binds bacteria, and bacterial binding or cross-linking to CD163 upregulates inflammatory cytokine production: TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6 [10]. SR-A (scavenger receptor A) and MARCO (macrophage receptor with collagenous structure) facilitate clearance of Neisseria meningitis, but deletion of SR-A enhances TNFα, IL-6, CXCL1 and CXCL2 secretion, and monocyte and polymorphonuclear cell migration to Niesseria meningitis [11]. In contrast, deletion of SR-A or MARCO markedly inhibited TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1 responses to the TLR3, ligand polyinosinic acid. CD36 is another scavenger receptor, binding selectively to oxidized LDL and phospholipids, presenting these molecules to TLR2 [12]. Thus scavenger receptors play several important roles in innate immune regulation by coordinating ligand delivery and modulating responses to TLRs.

INNATE IMMUNE LIGANDS

Increasingly, innate immune disturbances have become a focus in autoimmune illnesses, as it has become clear that such disturbances can precipitate autoantibody production and autoimmune disease. The association of certain chemical exposures with scleroderma-like illnesses further supports the notion that non-antigen specific innate immune responses to inflammatory stimuli might cause fibrotic disease like SSc. If one accepts that SSc is driven by activation of the innate immune system, the next question is, what are the source or sources of this activation? Innate immune ligands might originate from infections, other non-infectious exogenous ligands or endogenous ligands. Which of these are most important in SSc remains uncertain at present.

Microbial Derived Innate Immune Agonists

Activation of TLRs, RLRs, NLRs and scavenger receptors represent the first line defense against microbial infections. The difference in structure, the cellular location, as well as the complexity of downstream signaling by TLR and non-TLRs allows the immune system to respond differently to different pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites [13]. TLR1,2,4,5, and 6, are primarily committed to the recognition of various bacterial components and are mainly localized on the cell surface. Peptidoglycan, a component of gram-positive bacteria, and a component of mycobacteria, lipoarabinomannan (LAM), are sensed by TLR2 [14, 15]. TLR2, in conjunction with TLR1 or TLR6, recognizes diacyl or triacyllipopetides on bacteria, mycobacteria, and mycoplasma [16]. However, in vivo studies show that TLR2 and TLR6 also play essential roles in controlling some viral infections, and specific viral products such as the protein F of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the hemoagglutinin protein of the Measles virus and vaccinia virus, and thegB protein of human CMV (HCMV) can be sensed by TLR2 [13, 16-20]. Moreover infections from protozoa that are rich in unsaturated alkylacylglycerol and lipophosphoglycan (LPG), like Trypanosome and Leishmania species, are also sensed by TLR2 [13]. LPS a major cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria is sensed by TLR4 [21, 22]. TLR5 binds the flagellin protein expressed by flagellated bacteria. Activation of TLR1, TLR2, TLR4 and TLR5, mainly induces the production of inflammatory cytokines, whereas TLR4 also induces type I interferon.

Nucleic acids (single-stranded, double-stranded RNA or DNA derived from viruses) are recognized by several TLRs, primarily localized in an intracellular, endosomal compartment. RNA from RNA viruses, or from replicating DNA viruses or bacteria that activate the host enzyme DNA-dependent RNA polymerase III can be sensed by TLR3, RIG-I (double-stranded RNA), TLR7 and/or TLR8 (single-stranded RNA)[23, 24]. Specifically TLR3 has been implicated in innate immune activation by influenza virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), and murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) [25]. Recently it has been shown that non-coding RNA, specifically EBER from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and micro-RNAs from several viruses can also be sensed by TLR3 and RIG-I [26, 27]. In addition, several synthetic antiviral compounds, such as polyIC, and R848, imiquimod and loxoribineactivate TLR3, and TLR7 and TLR8, respectively [13, 16-18].

TLR9 senses bacterial and viral genomic DNA rich in unmethylated CpG, as well as synthetic oligonucleotides containing CpG motifs. Activation of TLR3, 7 and/or 9 induces the production of type I interferon by immune and non-immune cells [13, 16-18].

Environmental Derived Innate Immune Agonists

Several environmental exposures have been linked to fibrosis. Environmental or occupational exposure to silica dust leads to fibrosis [28], and in murine models activates inflammation and fibrosis through the inflammasome [29, 30]. The inflammasome also contributes to bleomycin-induced lung injury [31]. Bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis also depends on TLR signals and bleomycin has recently been described as a TLR2 ligand [32]. “Toxic oil syndrome” in Spain following ingestion of contaminated rapeseed oil caused a scleroderma-like illness implicated contaminating1,2-di-oleyl ester (DEPAP) and oleic anilide [33, 34] in causing the disease. Increased secretion of IL-1β and IL-6, and activation of NF-kB in mice treated with oleic anilide [35], development of high titer anti-nuclear antibodies in genetically predisposed MRL/lpr mice exposed to these oils [36], and the adjuvant activity of fatty acid esters [37] suggests that these chemicals may have caused disease by activating the innate immune system. Gadolinium exposure leading to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis appears to be mediated by macrophage activation of pro-fibrotic cytokine secretion [38], suggesting that gadolinium can also activate innate immunity in certain settings.

Matrix Derived TLR Ligands

Increasingly TLRs are understood to recognize endogenous ligands released during tissue injury. Hyaluronan generated during acute lung injury can activate TLR2 and TLR4, contributing to macrophage activation [39]. Biglycan, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan, can also act as a TLR2 or TLR4 ligand [40] and the extra domain A (EDA), found in one of the alternatively spliced forms of fibronectin, is a ligand of TLR4. Stimulation of TLRs by these matrix molecules provides another source for innate immune activation during inflammation and might act to initiate or perpetuate inflammation and fibrosis.

Toll-Like Receptors in Autoimmune Disease

Mammalian DNA and RNA do not normally engage nucleic acid sensitive TLRs in part because these receptors are sequestered in an endosomal compartment that normally excludes endogenous nucleic acids. However, SLE patient sera contain immune complexes (ICs) formed by autoantibodies to nucleic acids or nucleic acid binding protein/nucleic acid complexes that can act as endogenous ligands for nucleic acid sensing TLRs [41]. Autoantibodies in such ICs bind nucleic acid directly (anti-DNA antibodies), or indirectly by binding to nucleic acid binding proteins, such as Sm proteins. Dendritic and B cells can internalize these nucleic acid-containing ICs through Fc and surface immunoglobulin receptors, respectively [42-45], targeting the bound nucleic acid to the endosomal compartment, activating TLR7 (by RNA) or TLR9 (by DNA). TLR activation leads to dendritic cell production of interferon (IFN) and B cell maturation.

Similar activity has been found in SSc, patients suggesting that autoantibody containing ICs might activate innate immunity inSSc. Many of the proteins targeted by SSc-associated autoantibodies, strikingly, share the common feature of binding, directly or indirectly, to nucleic acids. One SSc-autoantibody target, topoisomerase-I, a DNA-nicking enzyme, also associates with a variety of proteins that bind RNA [46], suggesting that anti-topoisomerase ICs might bind DNA or RNA. As RNAse blocks innate immune activation by topoisomerase-containing ICs more efficiently than DNAase [47], TLR7/8, the single stranded RNA sensors, are most strongly implicated in topoisomerase-1 associated innate immune activation.

TISSUE SPECIFIC LINKS BETWEEN INNATE IMMUNITY AND FIBROSIS

Pulmonary Fibrosis

Lung fibrosis is generally progressive with a high mortality, the cause in most cases uncertain. A number of in vivo and in vitro observation support a role for TLRs in promoting fibrogenic responses, thought primarily mediated by fibroblasts, but also potentially involving other cell types such as macrophages or dendritic cells [48]. Recently activation of TLR3 by polyIC has been reported to increase lung inflammatory markers (RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein-1a, IL-8, ATP and CXCR2) released from epithelial cells in vitro [49]. In vivo studies have also shown that mice treated with polyIC have increased neutrophilic pulmonary inflammation, interstitial edema, and bronchiolar epithelial hypertrophy, suggesting that dsRNA generated during the replication of common pathogens associated with respiratory infections might interact with different pattern recognition receptors, impairing lung function [50].

Bleomycin (BLM)-induced fibrosis may also be mediated by TLR activation, in this case activation of TLR2, as TLR2 deficiency or treatment with a TLR2 antagonist not only protected but also reversed BLM-induced fibrosis [32]. Bleomycin also constitutes a major endogenous danger signal for activating the NALP3 inflammasome, leading to IL-1β production, lung inflammation and fibrosis, this effect precipitated by uric acid released from injured cells [51].

New findings have underlined a role for TLR9 in human pulmonary fibrosis. This TLR is overexpressed in pulmonary fibroblasts of patients with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and TLR9 agonists can induce fibroblast-myofibroblast differentiation [52, 53]. These data suggest that TLR9 can act as pathogenic sensor, recognizing microbial DNA, but can also have a role as profibrotic mediator, although the specific pathway, as well the cell types implicated in the fibrotic response remain unclear. Increased TLR3 and TLR9 have also found in the BAL fluid from patients with IPF [54]. Although TLR9 signaling in human IPF fibroblasts appears to drive a profibrotic response, TLR9 activation has shown a protective effect in lung fibrosis models in mice, indicating important unsettled issues remain regarding the role of TLR9 activation in fibrotic disease [55].

Liver Fibrosis

TLRs have been implicated in liver fibrosis, resulting from many common liver diseases, including viral, parasitic and toxin-induced hepatitis. Early reports implicated the release of intestinal LPS into the portal circulation in alcohol-induced liver injury and cirrhosis [56, 57]. Subsequent reports showed that TLR4 mediates inflammation and fibrosis in bile duct ligation and toxin-induced models of liver fibrosis [58]. However, a recent report shows that bile salts can also induce inflammation in the absence of TLR4 [59].

TLR4-bearing stellate cells respond to LPS, producing inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, but also promoting fibrosis [58, 60]. TLR2 and TLR4 have been particularly implicated in viral hepatitis. Lipopeptides derived from Hepatitis C activate TLR2 and TLR4 [61] and Hepatitis C Core protein stimulates TLR2 [62]. Further supporting the role of TLR4 in promoting fibrosis, it has been shown that deficiency in myelod differentiation factor-2 (MD-2), the co-receptor of TLR4, and TLR4 expression attenuates liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice affected by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [63].

TLR4 is also required for hepatic fibrosis associated with carbon tetrachloride [64]. In this model ST2-Fc apparently acting through the IL-33 receptor, markedly enhanced secretion of IL-4 and IL-13, exacerbating IL-4Rα-mediated fibrosis. In contrast, other studies have shown that TLR9 mediates fibrosis in mice treated will carbon tetrachloride, DNA released from apoptotic cells stimulating stellate cell production of smooth muscle actin, a marker of myofibroblasts [65].

Abrogation of normal protective responses may be particularly important in responses to viral infections. PolyIC protects mice from LPS induced hepatic injury, through downregulation of TLR4 [66]. Hepatitis B surface antigen suppresses TLR9 ligand mediated IFNα production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells [67]. Thus, although multiple TLRs have been implicated in liver inflammation and fibrosis, the net effects of microbial components on inflammation and fibrosis are complex and in many cases may involve multiple innate immune receptors, coordinating or opposing effects on inflammation and fibrosis.

Renal Fibrosis

TLR2 and TLR4 have both been implicated in nephrogenic fibrosis following unilateral ureteral obstruction [68, 69], with deletion of each receptor shown to ameliorate fibrosis. Deletion of TLR4 was reported to ameliorate fibrosis, but altered neither smad2 phosphorylation nor TGF-β levels. These effects of TLR2 or TLR4 deletion on unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced fibrosis have not been seen by others, where similar experiments showed no effect of TLR8 deletion [70].

Skin Fibrosis

Our group has shown that chronic administration of polyIC induces dermal fibrosis that is at least partially mediated by TGF-β[71]. The effect of polyIC on skin was partially, but not completely, blocked in TICAM-deficient mice, suggesting that RNA sensors in addition to TLR3 are responsible for inflammation and fibrosis in this model. Increased expression of IFN-regulated genes in SSc skin is consistent with the notion of a TLR-mediated stimulus, however, the source of TLR activation and the TLR(s) most important in SSc-associated dermal fibrosis remain uncertain. TLR4 activation may also play a role in skin fibrosis, as fibroblasts in hypertrophic scars express increased levels of TLR4 and make increased inflammatory cytokines upon LPS stimulation [72].

PROFIBROTIC CYTOKINES AND INNATE IMMUNE RESPONSES

In many cases TGFβ likely mediates innate immune stimulated fibrosis [58], and increasingly links between innate immune stimuli for other profibrotic cytokines are being clarified. Inflammatory cytokines produced by TLR activation, such as IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, IFNs and IL-12 may also play important profibrotic roles, by regulating TGFβ activation or stimulating other profibrotic mediators. In addition, recent studies have suggested that TLR activation might directly stimulate fibrosis, through direct actions on fibroblasts, including fibroblast conversion to profibrotic myofibroblasts through TLR3 [73] or TLR9 [65] activation.

Transforming Growth Factor-β

Several groups have shown that TLR4 activation augments TGF-β activity. Unfortunately direct assessments of TGF-β’s profibrotic effect are problematic, as the most important checkpoint for TGF-β is its activation and this is difficult to measure. Other measures, TGF-β mRNA or protein levels are of relatively little relevance as they may not reflect the impact of this cytokine on target cells. Most studies have relied upon TGFβ-regulated gene expression or phospho-smad 2/3 as surrogates, with some inherent uncertainty related to these measures. From this standpoint the study of TGF-β reasonably focuses on its activators. Although several activating proteins and mechanisms of TGF-β activation have been proposed, this has remained an area of intense uncertainty. The most acceptable paradigm at present is that TGF-β can be activated through any of several mechanisms, including increased cell tension, integrins and proteases (see reviews: [74, 75]). Which of any of these are important in a given inflammatory setting in most cases remains uncertain.

As described below, Kitamura et al. have recently attributed IL-1 activation of TGF-β to upregulated αvβ8 integrin expression [76], while others have reported that αvβ5 and αvβ6 activate TGF-β in IL-1β-mediated pulmonary fibrosis [77]. These observations might reflect molecular redundancy in TGF-β activation, or direct versus indirect effects of these integrins. Favoring a direct role for αvβ8 in TGF-β activation, its profibrotic effect was established by selective β8 deletion in fibroblasts, suggesting that fibroblast αvβ8 contributes locally to TGF-β activation. On the other hand, αvβ6 has also been implicated in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis [78]. Thus, upregulated integrin receptors provide a mechanism for TGF-β activation during inflammation. Ongoing development of integrin-blocking therapeutics should clarify the importance of this mechanism in activation of TGF-β in human fibrotic diseases.

Altered intracellular mediators may also sensitize cells to TGF-β. In hepatic fibrosis LPS downregulates Bambi through a Myd88 dependent pathway, sensitizing cells to TGF-β [58]. However, TRIF-mediated signaling also contributes to hepatic fibrosis in this model [60]. How innate immune and TGF-β signals interact inside the cell is an area that needs further exploration.

Interleukin-1

Interest in IL-1β has increased due to the new understandings of its inflammasome-mediated activation. Interleukin-1β plays a key role in both lung fibrosis stimulated by silica or bleomycin, both blocked in Nalp3-deficient mice [29, 79]. The mechanism linking IL-1β to fibrosis in these diseases is uncertain, but involves TGF-β/smad3-dependant stimulation [80]. In vitro IL-1β directly stimulates dermal fibroblast collagen production, but more potently stimulates collagenase activity, suggesting that its direct effect on collagen may be catabolic [81].

IL-1β deficiency also ameliorates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, and IL-1β alone can induce lung inflammation and fibrosis [80]. This latter model of lung fibrosis involves IL-17 production, withTGF-β possibly playing a key role upstream of IL17 in TH17 cell polarization and/or in mediating the pro-fibrotic effects of IL-17[82, 83]. Other recent studies in an adenoviral delivered model of IL-1β have implicated upregulated αvβ8 integrin expression in IL-1β mediated activation of TGF-β [76], fibroblast-specific deletion of the β8 integrin subunit blocking fibrosis, but also inhibiting TH1 and TH17 cell responses, and dendritic cell migration.

Interleukin-4 and -13

IL-4 and more consistently IL-13 have been implicated in fibrosis in several animal models, including colitis [84], pulmonary fibrosis [85], and schistosomiasis [86]. Transgenic expression of IL-13 leads to pulmonary fibrosis that is MMP-9 and TGF-β dependent [85], while IL-13 induced fibrosis in schistosomiasis is TGFβ-independent [87].

Although IL-13 is typically thought of as a lymphocyte derived, TH2 cytokine, it can also apparently be secreted by cells of the innate immune system, as skin fibrosis induced by bleomycin is blocked in IL4Rα1 deficient but not rag2 deficient mice [88]. How the innate immune system induces IL-13 is uncertain, but certain cytokines are emerging as candidate mediators. Thymic stromal lymphopoeitin (TSLP) induces IL-13 and its profibrotic effect is partially ameliorated in IL-4 and IL-13 deficient mice [89]. Surprisingly, however, IL-13 induced skin fibrosis depends on TSLP [90], suggesting autoregulatory interactions between these two cytokines. IL-33 administered subcutaneously also stimulates IL-13 by eosinophils and dermal fibrosis [91]. ST2, the IL-33 receptor, is found on T cells, but also on phagocytes, where it acts as an endogenous inhibitor of TLR2 and TLR4 responses and contributes to phagocyte function [92, 93].

Interleukin-6

IL-6 is strongly upregulated by TLR activation of many cell types. Bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis and carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis are attenuated in IL-6 deficient mice [94, 95]. However, transgenic overexpression of IL-6 in the skin does not cause skin fibrosis [96]. In vitro IL-6 stimulates fibroblast collagen production, but not as potently as IL-1β [97].

Interferons

SSc patients show increased expression of interferon-responsive genes, known as the interferon “signature” [98, 99]. IFNs include type I, type II and more recently identified type III IFNs. The type-I IFNs include 13, mostly co-regulated, IFNα subtypes, and IFNβ, signaling through a common receptor. Dendritic cells, particularly plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), are the major source of IFNα, secreting high amounts of IFN upon TLR7 or TLR9 activation. On the other hand, a range of TLR ligands can stimulate non-immune cells including fibroblasts to produce IFNβ [71]. TH1 and NK cells are the primary sources of IFNγ.

As the type I IFNs, IFNα and IFNβ, stimulate the same receptor, and type I and type II IFNs stimulate a similar set of genes, it is not possible to tell clearly from the pattern of PBMC interferon-responsive gene expression which IFN is responsible for the IFN signature in SSc patients. However, if similar mechanisms as those in SLE stimulate the IFN signature in SSc patients, then it is primarily due to IFNα, implicating plasmacytoid dendritic cells, the major cellular source of IFNα. Sera or purified immunoglobulin from SSc patients can stimulate IFNα by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [47]. This activity is mainly found in sera containing autoantibodies to topoisomerase, suggesting that ICs in SSc stimulate endosomal TLRs after Fc-mediated internalization by pDCs [43]. IFNs block the effects of TGF-β on fibrosis, suggesting that they might actually ameliorate this aspect of SSc pathogenesis. However, the use of IFNs in clinical trials has not shown any significant inhibition of collagen synthesis and instead suggested that IFN treatment aggravated disease activity in some SSc patients [100], indicating that impairment of IFNs might promote progression of the disease. Furthermore, as TLR activation of dendritic cells and macrophages also stimulates IL-1β, TNFα and IL-6 production, these or other undefined mediators might be more important in driving fibrosis in SSc.

CONCLUSIONS

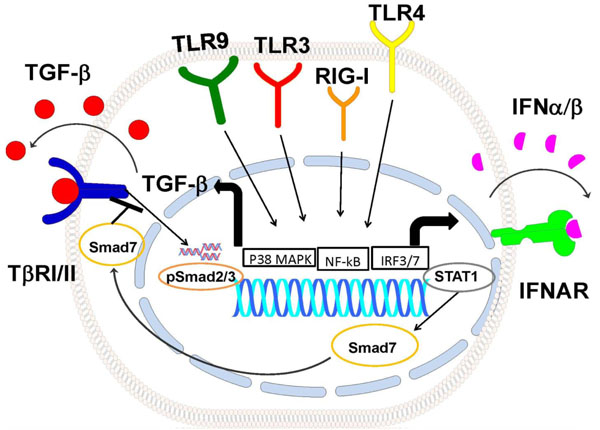

Multiple independent studies show that innate immune sensors can stimulate fibrosis through a variety of differing mechanisms. TLRs and non-TLR receptor ligands may singly or in combination promote fibrosis by stimulating secretion of profibrotic cytokines, by upregulating TGF-β activators, or by activating profibroticintracellular signals (Fig. 1). Matrix molecules and circulating innate immune activators in SSc patients suggest possible roles for TLR2 and TLR4 in this disease. Environmentally induced scleroderma-like illnesses highlight the potential importance of inflammasome activation and IL-1β in fibrosis.

Model of TLRpathways how regulate TGFb signaling. Activation of TLR9, TLR3, RIG-I and TLR4 pathways induce TGFb production possibly through p38 MAPK and NF-κB activation. TGFb1 autocrine/paracrine loop activates Smad2/3, TLRs also induce the IFN-β autocrine/paracrine loop, activating Stat1 and inducing Smad7. Smad7 inhibits activation of TGFβ signaling. TβRI/II: TGFβRecptorI/II, IFNAR: Type I Interferon Receptor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This review was supported by:Norma Nadeau/Mary Van Neste Research Grant” New England chapter of the Scleroderma Foundation to GA Farina; NIH grant 5P50AR0 60780-02; 5P30AR0 61271-02 and 5R01AR051089-07 to Robert Lafyatis

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Declared none.