Vitamin D and Spondyloarthritis: Review of the Literature

Abstract

Background:

Spondyloarthritides (SpAs) encompass heterogeneous diseases sharing similar genetic background, pathogenic mechanisms, and phenotypic features. Vitamin D is essential for calcium metabolism and skeletal homeostasis. Some recent evidences reported supplemental functions of vitamin D, such as modulation of inflammatory reactions.

Objective:

To analyze published data about a possible association between vitamin D and SpAs.

Results:

Vitamin D could play a role in immune reactions, influencing both immune and adaptive response. Vitamin D deficiency is more frequent in SpAs than in general population: an active and more severe disease infers patients’ mobility and reduces sunlight exposure. Quiescent inflammatory bowel disease, frequently associated with SpAs, could worsen vitamin D deficiency. All the parameters related to UVB exposure are the most important determinants for vitamin D status and need to be considered evaluating the vitamin D levels in SpAs.

Apart from musculoskeletal problems, patients affected by SpAs frequently suffer from other comorbidities, especially cardiovascular diseases and osteoporosis, and vitamin D status could have a relevance in this field. Bone is involved in SpAs with a dualistic role, coexisting trabecular bone resorption and new bone formation.

It seems rational to monitor vitamin D levels in SpA subjects and to target it to global health threshold.

Conclusion:

Literature data were not completely in agreement about a possible relation between poor vitamin D status and onset or worse disease course of SpAs. In fact, these results come from cross-sectional studies, which affect our ability to infer causality. Therefore, large, randomized controlled trials are needed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Spondyloarthritides (SpAs) encompass an interrelated group of heterogeneous clinical entities sharing similar genetic background, pathogenic mechanisms, and phenotypic features [1]. According to more recent classification, SpAs include axial-spondyloarthritis (axSpA) as both radiographic (Ankylosing Spondylitis [AS]) and non-radiographic (nr-axSpA) form, Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA), Reactive Arthritis (ReA), enteropathic arthritis, juvenile spondyloarthritis, and what has traditionally been referred to as undifferentiated seronegative arthritis [2]. The most important clinical manifestations of SpAs include inflammatory back pain, asymmetric peripheral oligoarthritis, predominantly in lower limbs, enthesitis, and sacroiliitis. Moreover, SpAs may also be complicated by extra-articular involvement, such as anterior uveitis, psoriasis, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, and osteoporosis [3, 4]. The latter may be related to both the hyper-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Tumour Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α) and the role of vitamin D in affecting bone mineral density [5].

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone essential for the regulation of the calcium metabolism and skeletal homeostasis [6]. We distinguish two forms of vitamin D, cholecalciferol (vitamin D3), which derives from animals, and ergocalciferol (vitamin D2), that derives from plants, as well as vitamin D metabolites. The former comes from the endogenous conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol into previtamin D in the skin upon ultraviolet B radiations, and the latter arises from the dietary intake. These precursors switch into the active form, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D) by successive hydroxylation, first in the liver to 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D), subsequently in the kidneys to 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) [6, 7]. Due to the short half-life of 1,25(OH)2D, almost 4 hours, serum 25(OH)D is the metabolite used to measure the vitamin D status of individuals; in fact, it is the major circulating form with a long half-life (2-3 weeks) [8].

Recent evidence has shed light on the additional function of vitamin D, such as a significant role in the regulation of both adaptive and innate immune system, modulating inflammatory reactions [9-11]. Furthermore, epidemiological studies evidenced a higher prevalence of autoimmune and rheumatic diseases among people living at increasing latitude [12], where vitamin D deficiency, caused by reduced ultraviolet B exposure, may play a role. Moreover, several authors pointed out a potential association between a poor vitamin D status and different chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and inflammatory diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis, and Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) [6, 7, 13].

The aim of this review is to analyze data published on the relationship between vitamin D and SpAs, evaluating their potential epidemiological and pathophysiological connection and the implication for the management and treatment.

2. VITAMIN D, SPONDYLOARTHRITIS AND AUTOIMMUNE SYSTEM

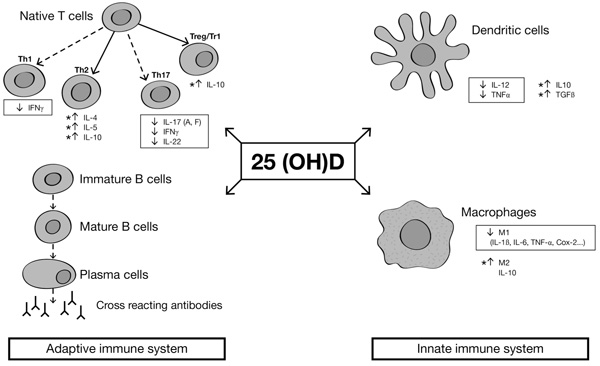

There is evidence that vitamin D exerts both inhibiting and activating actions in the immune system [9, 14]. Monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells express 1-alpha-hydroxylase (Cytochrome P450 Family 27 Subfamily B -CYP27B-) Fig. (1). This gene can lead to the activation of 25(OH)D into the 1,25(OH)2D, which has inhibiting effects on dendritic cells, promoting monocyte to macrophage differentiation and producing immunosuppressant cytokines [15]. Moreover, macrophages stimulated by 1,25(OH)2D increase their phagocytic capacity and kill bacteria, particularly mycobacteria [16]. A genetic association has been found between a CYP27B1-gene and HLA-B27 anterior uveitis. A study compared three different groups: 159 HLA-B27-positive subjects with anterior uveitis, 138 HLA-B27-negative healthy controls and 100 HLA-B27 positive healthy controls. Steinwender and colleagues found a high prevalence of the G allele in HLA-B27 subjects with anterior uveitis compared to HLA-B27 positive healthy controls [17]. A few concerns about this study are related to the exclusion of the HLA-B27 negative controls, so it remains difficult to determine if this link is specific for HLA-B27 uveitis or only for uveitis. Another study by Mitulescu and coauthors, reported a negative correlation between vitamin D levels and acute anterior uveitis, linking altered vitamin D metabolism to the development of the ocular disease, which is an extra-articular manifestation often associated in SpAs [18].

Cells of the innate immune system, i.e. dendritic cells and macrophages, also express Vitamin D Receptor (VDR). Fok1, a genetic VDR polymorphism detected from genomic DNA from peripheral leukocytes, was associated with elevated acute phase reactant levels and spinal bone mass density in 71 axial SpA patients, compared to healthy controls [19]. Truthfully, such links between disease activity and VDR polymorphism have been described also in rheumatoid arthritis patients, suggesting that vitamin D metabolism can exert a broad spectrum of actions in inflammatory diseases.

Furhtermore, it has been described a genetic association between the Vitamin D-Binding Protein (VDBP) and some SpA phenotypes such as uveitis (OR 2.04; p =0.02) or peripheral joint involvement (OR 0.6, p =0.01) compared to healthy controls [20].

Beyond its effect on the innate immune system, 1, 25(OH)2D reduces pro-inflammatory T helper 1 and Th17 cell activity, decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e. interleukin 1, TNF- α, interleukin -6, and interleukin-17). Besides, 1,25(OH)2D acts on T regulatory cells and Th2 responses, raising blood levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-10) [9]. Taking into account its autocrine action, 1,25(OH)2D lowers the release of autoantibodies and immunoglobulins in the plasma, contributing to modulate autoimmune and autoinflammatory response in immune-mediated inflammatory disorders [9, 14, 21].

Give the aforementioned, vitamin D could play a role in immune reactions, impairing the interaction between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, but these evidences come from cross sectional studies and had not been confirmed in genome-wide association studies [22]. Therefore, these speculations about the interplay between vitamin D, immune system and SpA need to be further investigated; randomized clinical trials are needed, possibly carried out during the early stages of the disease to control progression, or in the longstanding forms, to prevent disease flares.

3. VITAMIN D DEFICIENCY AND SPONDYLOARTHRITIS: EPIDEMIOLOGICAL DATA AND DISEASE ACTIVITY

Several studies highlighted that vitamin D deficiency is more frequent in patients affected by SpA compared to the general population or healthy controls. In 161 SpA patients, 25(OH)D serum levels were found significantly lower compared with unaffected subjects [23]. In the French DESIR cohort, including more than 700 patients with a recent onset of inflammatory back pain suggestive of SpA, severe vitamin D deficiency was found in 11.7% of patients compared with 5% in the French population. A recent study describing the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency on the ASAS-COMOSPA cohort has been published. In this international cross-sectional study, vitamin D deficiency was observed in 51,2% of 1030 patients, who were not receiving vitamin D supplementation. This deficit was independently associated with the presence of sacroiliitis (OR=2.1 [95%CI 1.3; 3.3]) and seasonal variation (OR=1.88, [95%CI 1.2;2.9]); suggesting that vitamin D deficiency is related to more severe forms of SpAs and seasonal fluctuation. No relation was found between vitamin D levels and comorbidities [24].

Patients who had baseline serum levels of 25(OH)D lower than 20 ng/mL showed a significant association with X-ray sacroiliitis (104/358 vs 81/342, p <0.03), higher Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), and elevated Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) (226/358 vs 193/342, p< 0.03), even when these results were adjusted for season or ethnicity. This trend between vitamin D deficiency and mean values of disease activity/severity scores was further confirmed during the two-year follow-up period [25]. Similarly, other cross-sectional studies confirmed such evidence in cohorts including population with different ethnicity [26, 27].

Conversely, opposite findings were shown in another study, which included 203 AS patients and 120 healthy controls. Authors did not report data indicating a poorer vitamin D status in AS subjects. Moreover, they found no relation between serum 25(OH)D levels and disease activity, seasonal dosing, and physical function [28]. Several studies are consistent with Klingberg and coauthor findings. Arends and colleagues evaluated one hundred and twenty-eight consecutive Dutch outpatients with active AS. They investigated the link between Bone Mineral Density (BMD), bone turnover markers (such as procollagen type 1 N-terminal peptide, osteocalcin, and bone resorption marker serum C-telopeptides of type I collagen), and vitamin D status. Furthermore, they assess clinical scores of disease activity and physical function in order to identify parameters that could be related to low BMD. According to their results, increased bone turnover, inflammation, and low vitamin D levels could play a role in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis observed in AS, but ESR, CRP, ASDAS, or Bath AS Functional Index were not significantly correlated with BMD T-scores [29].

Another study investigated the correlation between osteoporosis, vitamin D and disease activity in a hundred patients with AS compared to 58 healthy controls. AS subjects were further divided into two groups as with or without osteoporosis, according to lateral lumbar BMD values. Authors found that BASDAI scores were higher in the AS osteoporotic group, but the difference between AS osteoporotic, non osteoporotic and healthy controls was not statistically significant (p >0.05). Only the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) scores were significantly higher in patients with osteoporosis (5.28±2.45 vs 4.00±2.46, p <0.05); on the other hand, there was non difference in terms of (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) scores (5.38±2.25 vs 4.86±1.97, p >0.05). In patients with AS, a negative correlation without statistical significance was noted between the serum 25(OH)D level and ESR, CRP levels determining disease activity (r=-0.181, and r=-0.095, p >0.05, respectively). However, no significant correlation was detected between 25(OH)D and BASDAI scores (r=0.011, P >0.05) [30].

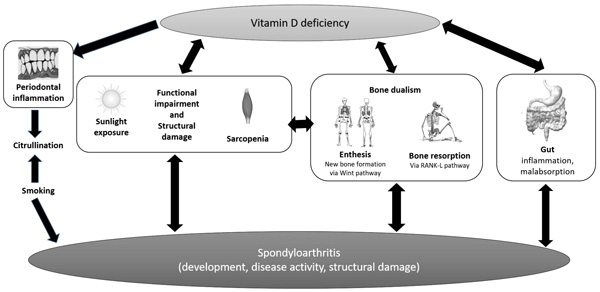

These controversial results on the complex relationship between vitamin D deficiency and SpAs should be read in light of several confounding factors that need to be considered. Periodontal inflammation could be promoted by vitamin D deficiency, inducing citrullination of peptides such as vimentin, as demonstrated also in RA Fig. (2). According to some reports, citrullinated vimentin is associated with radiological disease progression even in SpAs [31] and vitamin D deficiency could be related to X-ray sacroiliitis [25]. Some authors linked vitamin D status with worse disease activity/severity; reciprocally, functional impairment and structural damage could worsen vitamin D deficiency by reducing sunlight exposure. In this perspective, lower serum vitamin D status could be the result of disease activity than a cause thereof.

One study detected a high prevalence of anti-htTG antibodies, a marker of celiac disease, in AS subjects, raising concerns on a possible risk of malabsorption-related low vitamin D levels [32]; in fact, subclinical intestinal inflammation is common in AS, about 40-60% according to earlier endoscopic studies [5, 33, 34]. Furthermore, disease activity scored by BASDAI is independently associated with gut inflammation in axial SpA [35] and inflamed gut macrophages produce IL-23, which is notably up-regulated in SpA, inducing Th-17 response in enthesis through a specific subset of T-cells [36]. Taking all these data together, malabsorption could contribute to worsening vitamin D deficiency.

4. VITAMIN D DEFICIENCY AND SPONDYLOARTHRITIS: THE INFLUENCE ON BONE METABOLISM

In SpA, bone involvement is dual: on the one hand, trabecular bone resorption by osteoclasts is mediated by the effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF on the RANK ligand pathway [37, 38]; on the other hand, the peculiar new bone formation of SpAs is most notably driven by Wnt signaling [39, 40], than by bone morphogenetic proteins [41], and transforming growth factor β [42]. A longitudinal study evaluated the possible role of Sclerostin (SOST), a potent Wnt inhibitor, during anti-TNFα therapy in 30 patient affected by AS. Authors reported that SOST levels significantly increased after 1 year of anti-TNFα therapy (60.5±32.7 vs 72.7±31.9, p <0.001), concomitantly with a gradual increase of spine bone mineral density (p <0.001), suggesting that SOST could underlie the persistent syndesmophyte formation reported in patients with AS [43]. It has been demonstrated that parathyroid hormone down-regulate SOST expression by osteocytes both locally [44] and in the serum [45]. Since vitamin D deficiency may cause secondary hyperparathyroidism, leading to increase bone loss, it could be reasonable to monitor and supplement vitamin D in SpA patients.

5. THE IMPACT OF VITAMIN D ON AND SPA COMORBIDITIES: WHAT EVIDENCE?

SpA patients, apart from musculoskeletal involvement, frequently suffer from other comorbidities, and this risk is higher in SpA than in the general population, especially for some specific disorders (e.g., cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and osteoporosis) [46-50]. Such an increased risk for SpA patients can be related to the therapies used to obtain disease control (i.e., Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids) and also by other variables often observed in patients with SpA (for example, metabolic syndrome, systemic inflammation). In addition, in AS and/or PsA, it has been described an excess of mortality [46-48] that can be related not only to an increased risk of CVD [51-53], but also to osteoporosis [54], mostly for the complications following vertebral fractures [55, 56].

5.1. Cardiovascular Risk

Vitamin D deficiency is associated with various vascular dysfunction such as arterial stiffening and left ventricular hypertrophy [57]. Moreover, low levels of vitamin D might be involved in worsening of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia control, with a consequent increase of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [58, 59]. Some studies highlighted the inverse relationship between vitamin D deficiency and elevated blood pressure, suggesting a possible involvement of vitamin D metabolism in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Such effect on blood pressure could be explained by the key modulating effects of vitamin D on the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system; in fact, vitamin D deficiency may promote a sustained activation of this axis [60].

However, meta-analyses of clinical trials evaluating vitamin D supplementation failed their goals on CVD risk factor improvement [61-66]. Wang and coauthors published a meta-analysis of 17 prospective cohort studies and randomized trials. According to their findings, moderate to high doses of vitamin D supplements might reduce cardiovascular risk, especially for dialyzed patients [67]. Nevertheless, this evidence is quite poor; in fact, only one study involving the general population [68] showed a reduction in ischemic cardiovascular disease after vitamin D supplementation.

Cytokines in the boxes are pro-inflammatory cytokines, while asterisks are next to anti-inflammatory cytokines. Dashed arrows indicate decreased differentiation, and continue arrows indicate increased differentiation.

Periodontal inflammation could be promoted by vitamin D deficiency, inducing citrullination of peptides, which is associated with radiological disease progression in SpA. Vitamin D status can be the result of a worse disease activity/severity course; reciprocally, functional impairment and structural damage could worse vitamin D deficiency by reducing sunlight exposure. High frequency of silent inflammatory bowel disease are reported in SpA with a consequent risk of malabsorption, which could contribute in worsening vitamin D deficiency. In SpA, bone involvement is dual: on the one hand, trabecular bone resorption is stimulated by cytokines and RANK ligand pathway; on the other hand, the peculiar new bone formation is most notably driven by Wnt signaling.

It should be stressed that most of these trials on the therapeutic effect of vitamin D were designed to investigate protective skeletal effects on quite elderly people (mean age exceeded 70 years), mostly women, with established CVD or other risk factors [65]. To date, among the available randomized trials on cardiovascular outcomes, less than one-half were designed without predefined cardiovascular endpoint; so any inference could be misleading.

Controversial results suggest that the maintenance of ideal 25(OH)D levels may reduce the risk of stroke among a representative sample of the US population [69]. Besides, AS patients have 1.6-1.9 fold increased risk for cardiovascular diseases than the general population [7]. Beyond traditional CVD risk factors (i.e. smoking, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension), chronic inflammation can play as a further determinant.

5.2. Osteoporosis

Although new bone formation may be considered as a hallmark of AS, osteoporosis is a well-recognized comorbidity, which occurs even in the early, mild form of AS and increases the risk of fractures. Radiographic bone loss has already been recognized in pre-densitometric studies [70, 71], and osteoporosis was connected with disease duration and older age. Bone loss starts rapidly in AS, at the beginning of the disease, involving trabecular bone [72], as not only a consequence of spinal stiffness or immobility. As a direct consequence of osteoporosis, vertebral fractures are frequently reported in AS, even if they are underestimated in clinical practice, due to misinterpretation of back pain that could be wrongly attributed to exacerbations of the spondylitic process instead to the fractures [73]. Moreover, fractures are associated with severe consequences in term of skeletal pain, stiffness, disability, physical deformity, disability, poor quality of life, need for long-term care assistance, and, last but not the least, financial burden [74-76]. Moreover, vertebral fractures may cause severe neurologic consequences and even increased mortality [75]. Another challenge consists of the diagnosis and surgical management of such fractures, because these patients frequently have a pre-existing skeletal involvement and several comorbidities [77]. A recently published meta-analysis evaluated the risk factors of fractures in AS. Pray and coauthors demonstrated that the main risk factors of vertebral fractures in SA are male sex, disease duration, modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score, Bath AS Radiology Index, and low BMD at the hip and distal forearm. To date, evidence on hip fracture risk in AS is inconsistent. Any inferences can be made regarding the effect of NSAIDs and TNF inhibitors on fracture risk, due to the lack of conclusive results [77].

As aforementioned, two opposite mechanisms affect bone metabolism in SpAs: a high incidence of osteoporosis and vertebral fracture risk and increased bone formation. Several factors can contribute to the high risk of osteoporosis and fractures, such as chronic inflammation, reduced motion or sedentary lifestyle due to pain and stiffness, or drug-induced osteoporosis [28, 29]. Vitamin D deficiency is a global health problem, as well as a common risk factor for osteoporosis. A most recent Cochrane analysis concluded on a reduction in hip and other fractures with low doses of vitamin D (about 10 μg daily) and calcium supplement [78]. According to a systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies, the prevalence of osteoporosis varied from 11.7%-to 34% and from 11% to 24.6% for fractures in axial-spondyloarthritis patients. Furthermore, authors described a low 25(OH)D status in axial SpA cohort compared to controls, as a high corticosteroids use and alcohol intake [79]. Moreover, another cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate the relationship between disease activity, radiographic changes, bone mineral density, and vertebral fractures showed vitamin D deficiency in 85.7% of 206 axial SpA patients.

A concern regarding all data published in osteoporosis and SpA is that the anterior-posterior lumbar spine evaluation can overestimate BMD status by the presence of syndesmophytes, ligament calcifications, and fusion of facet joints [80, 81]. Moreover, the only hip BMD measure could not be sufficient to assess properly osteoporosis in all AS-patients since bone loss may primarily occur in the spine [29, 80].

Low vitamin D levels were significantly associated with the presence of fractures (20.8 vs 18.04, p=0.049) [82]. Taking all these data together, it seems fundamental to properly assess bone metabolism and fracture risk in spondyloarthritis.

6. VITAMIN D AND SPONDYLOARTHRITIS: SUPPLEMENTATION TREATMENT

Adequate vitamin D intake is pivotal for optimal balance of mineral and skeletal metabolism. Nowadays, the ideal serum level of25(OH)D that should be reached when treating with vitamin D supplements is still a matter of debate. According to different guidelines, 50 or 75 nmol/L (i.e. 20-30 ng/mL) could be considered the threshold [83-85]. Screening of vitamin D status is recommended in the population at risk for deficiency, for example, chronic kidney diseases, osteoporosis, malabsorption, some lymphomas, or in case of drugs interacting with vitamin D metabolism, such as steroids, cholestyramine, AIDS medications [83].

Moreover, it is still a matter of debate if the target of 25(OH)D supplementation strategy could be the increase of 25(OH)D plasma level; in fact, according to a retrospective analysis on an heterogeneous group of rheumatic diseases, a more efficient way of monitoring 25(OH)D serum concentration could be parathyroid hormone (PTH) suppression [86]. Furthermore, a strategy evaluating a loading dose supplementation, followed by a daily dose, seemed to be more effective in normalizing plasma 25(OH)D and suppressing PTH concentrations in patients with rheumatic diseases. Again, the same authors supported the evidence that patients with rheumatic diseases seem to be more refractory to PTH suppression by vitamin D supplementation, that is probably why they need higher doses compared to non-rheumatic subjects [87]. Thus, 25(OH)D treatment should aim to normalize vitamin D levels and decrease PTH concentrations [88].

Even though it seems to be logical to monitor vitamin D status in SpA patients, benefits from a therapeutic effect of vitamin supplementation appear to be very modest, especially in the absence of well-conducted clinical trials. In fact, no longitudinal intervention study, with accurate sample size and design, has been carried out; so, it could be very risky to over- or misinterpret results coming from case series, case reports or cross sectional studies. Considering the lack of incontrovertible data, it seems to be rational to monitor 25(OH)D levels in SpA subjects and to target vitamin D global health threshold Table 1.

| Age | Dose |

|---|---|

| 0-1 year | 400-1000 IU/day |

| 1-18 years | 600-1000 IU/day |

| Adults | 800-1000 IU/day |

| 51-70 years | 800 IU/day |

| >70 years | 800 IU/day |

|

Osteoporotic patients with serum vitamin D<50 nmol/L Or <75 nmol/L in elderly with a high risk of falls and fractures |

800-1000 IU/day |

CONCLUSION

To conclude, latitude, season, clothing, skin pigmentation, time spent outdoor, and all the parameters related to UVB exposure are the most important determinants for serum 25(OH)D. Moreover, vitamin D metabolites are not easy to be dosed for several reasons. Given the above, a snapshot measurement of 25(OH)D without adjustment for or awareness of these confounding factors could mislead studies’ conclusions, introducing both bias and noise in cases and controls, making comparisons between countries complex. According to the literature data, patients affected by SpA seem to have lower 25(OH)D levels compared to healthy controls or general population. Moreover, several authors gave evidence for an inverse association between measures of disease activity and 25(OH)D levels. Studies were not completely in agreement about this issue and this discordance is not unexpected. In fact, all these data come from cross-sectional studies, which impairs the ability to infer causality. Indeed, SpA subjects suffer from an increased risk of osteoporosis. So far, realizing whether 25(OH)D is a risk factor for disease susceptibility is important, as a modification of levels may protect against disease development in at-risk individuals. Therefore, if vitamin D deficiency could predict a more severe disease, understanding this risk could lead to focus on new pathogenic mechanisms as well as cost-effective therapy approaches. Well-designed and well-executed studies are needed, in order to clarify vitamin D impact on several health issues, including the extra-skeletal effects of vitamin D deficiency. Large, randomized controlled clinical trials assessing the benefits of supplement vitamin D in SpA, outside the largely well-known skeleton effects, are still lacking.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared None