RESEARCH ARTICLE

Pregnancy Outcome in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is Improving: Results from a Case Control Study and Literature Review

Sai Yan Yuen, Adriana Krizova, Janine M Ouimet , Janet E Pope*

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2008Volume: 2

First Page: 89

Last Page: 98

Publisher ID: TORJ-2-89

DOI: 10.2174/1874312900802010089

Article History:

Received Date: 31/10/2008Revision Received Date: 12/11/2008

Acceptance Date: 16/11/2008

Electronic publication date: 31/12/2008

Collection year: 2008

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

Abstract

Objectives

For women who suffer from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), pregnancy can be a concern, placing the mother and fetus at risk. Our objectives were to assess the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome, disease flares, fertility rate, and co-morbidities in SLE women compared to healthy controls. We also systematically reviewed the literature available on pregnancy outcome in SLE to compare our results to other published data. Our hypothesis was that pregnancy outcome in SLE is improving over time.

Methods

A case-control study comparing self-report of the above-mentioned parameters in SLE (N=108) vs healthy controls or patients with non-inflammatory musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders (N=134) was performed. Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire. Proportions, means and odds ratios were calculated. We searched and quantified the literature on pregnancy outcome, lupus reactivation and fertility rate. Data were summarized and presented in mean % ± SEM and median % with interquartile range (IQR).

Results

Gynecological history, fertility rate and age at first pregnancy in SLE patients were comparable to controls. Eighteen percent of SLE patients reported a flare and 18% reported an improvement of symptoms during pregnancy. Twenty-four percent of lupus patients had at least one preterm delivery vs 5% in controls (OR =8.32, p = 0.0008), however other pregnancy outcomes (miscarriage, therapeutic abortion, stillbirth and neonatal death rate) did not differ between the groups. Thyroid problems were reported to be more likely in SLE patients (p = 0.02), but the prevalence of other co-morbidities was similar to controls. A literature review demonstrated that fertility was not affected in SLE patients. Lupus reactivations are common during pregnancy (36.5% ± SEM 3.3%). Most agreed that SLE pregnancies had more fetal loss (19.5% ± SEM 1.6%) and preterm births (25.5% ± SEM 2.2%) when compared to the general population. Over time, the rate of SLE peripartum flares has improved (p = 0.002) and the proportion of pregnancies resulting in live birth has increased (p = 0.024). The frequency of fetal death has not significantly changed. Our findings from the case-control study were, in general, consistent with the literature including the frequency of fetal death, neonatal death, live births and pregnancy rate.

Conclusion

Prematurity (25.5% ± SEM 2.2%) and fetal death (19.5% ± SEM 1.6%) in SLE pregnancy are still a concern. However, new strategies with respect to pregnancy timing and multidisciplinary care have improved maternal and fetal outcome in SLE.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a serious multi-system disease affecting predominantly women of childbearing age. Fertility of SLE patients is usually comparable to the general population. There have been improved outcomes and survival in SLE. Likewise, adequate obstetrical care and perinatal management might ensure a better pregnancy outcome.

Historically, fetal and maternal well being of patients with SLE seemed to be compromised to the extent that the medical community recommended against pregnancy in SLE patients. It was difficult to assess whether superimposing pregnancy was detrimental as the clinical outcome of non-pregnant SLE patients was poor [1, 2]. It seems that with better control of disease activity, pregnancy in SLE patients is no longer an absolute contraindication. However, fetal and maternal complications still exist. Careful planning of pregnancy coupled with multidisciplinary monitoring and treatment substantially decreases the risks for the mother and the infant [3].

In this article we report a case-control study on pregnancy outcome, disease flares, fertility rate, and co-morbidities comparing SLE patients vs healthy controls or patients with non-inflammatory musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders using a self-report questionnaire. We also compare our results to the current literature using a systematic quantitative approach. Our hypothesis was that pregnancy outcome is improving over time in SLE.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

A four-page questionnaire was sent to subjects with SLE and either healthy control subjects solicited from a newspaper advertisement or subjects who had non-inflammatory MSK disorders such as osteoarthritis, tendonitis and fibromyalgia. SLE patients and MSK patients were recruited from a single rheumatology clinic. This questionnaire contained 44 questions on socio-demographics and pregnancy history, and was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board of the University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. All SLE patients met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria [4]. All subjects were blinded as to the hypothesis and were sent the questionnaire packages. Two follow-ups were sent to non-respondents.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using JMP Statistical Discovery Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). For each survey question, unanswered questions were excluded from the analyses. Group means, proportions, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Statistical significance was accepted at p ≤ 0.05. Analyses were redone after adjusting for age.

We also assessed laboratory results for antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies and antiphospholipid antibodies (anticoagulant and anticardiolipin) in 36 patients from our lupus cohort. Standard assays were used for each type of antibody: immunofluorescent antinuclear antibody (ANA or FANA) test; ELISA for anti-dsDNA; lupus anticoagulant panel (activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT] and modified Russell viper venom time [RVVT], platelet neutralization procedure [PNP] or kaolin clotting time [KCT], etc., as appropriate); and ELISA for anticardiolipin antibodies.

A review of the literature on pregnancy outcome in SLE was performed. Original articles on fertility rate, lupus flares during pregnancy, prematurity and fetal losses were selected. The search was conducted using the Pubmed database available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?DB= pubmed. Terms used (in various combinations) were: systemic lupus erythematosus, pregnancy outcome, lupus pregnancy, fertility rate, prematurity, preterm delivery, fetal loss, fetal wastage (referred to as fetal death in this paper), fetal outcome, spontaneous abortions,miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, lupus flares, lupus nephritis. Due to the vast amount of literature available, some older and smaller studies were not included. Data reported from each article on pregnancy outcome, including fertility, parity, elective abortions, miscarriages, fetal loss, neonatal death, preterm or full birth rates and lupus flares were recorded. We calculated the mean % ± SEM and median % with interquartile range (IQR) for each subject. We then classified these articles into 3 subgroups according to their publication date to assess temporal trends. Findings were summarized and compared to those obtained from our case-control study.

RESULTS

The response rate was 72% for SLE subjects and 69% for controls. The mean age of SLE subjects was 42 ± SEM 1 years vs 38 ± SEM 1 years for controls. Controls were more likely to continue their education above high school (p = 0.0001), and lupus patients were more likely to be homemakers (p = 0.01). In terms of marital status, there were no differences between the groups. All data are summarized in Table 1.

Subjects` Characteristics and Results of Our Case-Control Study

| SLE N (%) | Controls N (%) | p-Value | OR | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 108 | 134 | |||

| Age (years) | 42 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 0.37 | ||

| Disease Duration (years) | 15 ± 1 | ||||

| Educational level High school Above high school |

52 (48) 56 (52) |

26 (19) 108 (81) |

0.0001 |

0.26 |

2.18-6.83 |

| Marital Status Never married Married,Living Common-law, Widowed Separated, Divorced, Remarried |

15 (14) 77 (71) 6 (15) |

25 (19) 84 (62) 25 (19) |

0.36 |

||

| Work experience Homemaker Working/Student |

21 (21) 81 (79) |

11 (9) 115 (91) |

0.01 |

2.7 | 1.24-5.93 |

| Ever pregnant | 83 (77) | 93 (69) | 0.15 | 1.5 | 0.85-2.73 |

| Symptoms before last pregnancy Yes No Unknown |

25 (30) 55 (66) 3 (4) |

||||

| DM | 4 (4) | 2 (1.5) | 0.28 | ||

| Hypertension | 23 (22) | 18 (13) | 0.10 | 1.76 | 0.90-3.48 |

| Thyroid Problems | 23 (21) | 14 (10) | 0.02 | 2.32 | 1.13-4.77 |

| Other Medical Problems | 57 (54) | 57 (43) | 0.09 | 1.55 | 0.93-2.59 |

| Onset of menarche (years) | 12.6 ± 0.1 | 12.2 ± 0.2 | 0.07 | ||

| Menopausal | 40 (38) | 32 (24) | 0.02 | 1.93 | 1.11-3.38 |

| Age at menopause * | 42 ± 1 | 43 ± 2 | 0.37 | ||

| Hysterectomy causing menopause in above group (%) | 21 (47) | 12 (39) | 0.29 | 1.39 | 0.55-3.51 |

| Hormone replacement therapy (ever used during menopause) | 29 (66) | 14 (47) | 0.10 | 2.21 | 0.85-5.71 |

| Irregular periods in non-menopausal | 10 of 44 (22) | 5 of 29 (17) | 0.57 | 1.4 | 0.43-4.7 |

| Mean age at 1st pregnancy (years) | 23 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 0.06 | ||

| Number of pregnancies per woman | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.17 | ||

| Number of children | 2.33 ± 0.1 | 2.05 ± 0.1 | 0.72 | ||

| Had child (ren) (% out of those pregnant) | 78 (93) | 89 (95) | 0.60 | ||

| No children | 5 (5) | 4 (5) | 0.74 | ||

| Miscarriage (at least one) | 26 (31) | 28 (30) | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.50-1.79 |

| Therapeutic abortion | 7 (8) | 8 (8) | 0.53 | 1.03 | 0.36-2.99 |

| Ever had a stillborn child | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.22 | ||

| Neonatal death (<3 months) | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | 0.13 | ||

| At least one preterm birth | 20 (24) | 5 (5) | 0.0008 | 8.32 | 3.06-22.66 |

| Gestational Diabetes | 7 (9) | 5 (5) | 0.42 | 1.62 | 0.49-5.33 |

| High blood pressure / Toxemia during pregnancy | 23 (28) | 20 (22) | 0.36 | 1.38 | 0.69-2.75 |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 35 (42) | 22 (24) | 0.009 | 2.35 | 1.23-4.49 |

| Alcohol during pregnancy | 5 (6) | 10 (11) | 0.26 | 0.53 | 0.17-1.62 |

| Other health problems during pregnancy | 30 (37) | 24 (26) | 0.11 | 1.69 | 0.89-3.23 |

| SLE flare during pregnancy | 10 (18) | As defined by patients | |||

| SLE improved during pregnancy | 10 (18) | ||||

| Contraception use (ever, any, including OCP) | 96 (89) | 128 (96) | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.11-0.92 |

| OCP use | 66 (49) | 47 (44) | 0.38 | 0.8 | 0.48-1.32 |

| Duration of OCP use (mean ± SEM in months) | 56 ± 5.7 | 72 ± 5.5 | 0.0001 | 0.58-0.65 | |

| Tubal Ligation | 33 (32) | 30 (23) | 0.11 | 1.60 | 0.89-2.85 |

| At least 6 months of infertility | 32 (33) | 41 (32) | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.59-1.83 |

| Unable to have children because of infertility | 18 (19) | 30 (24) | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.39-1.44 |

| Ever taken fertility medications | 5 (5) | 5 (4) | 0.73 | 1.25 | 0.35-4.44 |

| Infertility problems – partner Yes No Not known |

5 (5) 63 (64) 31 (31) |

6 (5) 74 (59) 45 (36) |

0.76 |

0.98 |

0.29-3.36 |

Results are given in % or mean ± SEM, unless indicated otherwise.

OR= odds ratios: SLE vs controls

OCP= oral contraceptive pills

* Most were not menopausal, so age should increase over time

Summary of Pregnancy Outcomes, Fertility Rate and Flares Presented in Mean (%) ± SEM from Published Studies Compared to Our Present Case- Control Study Findings

| N | Literature Review |

Present Study-SLE Cases |

Present Study-Controls |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elective termination (%) |

44 | 10.5 ± 1.5 | 2.9 | 4.0 |

| Fetal wastage (%) | 45 | 19.5 ± 1.6 | 18.3 | 16.6 |

| Neonatal death (%) | 39 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| Preterm birth (%) | 43 | 25.5 ± 2.2 | 9.5 | 4.9 |

| Full term birth (%) | 44 | 49.0 ± 2.5 | 69.3 | 74.5 |

| Live birth (%) | 50 | 72.3 ± 1.9 | 78.8 | 79.4 |

| Pregnancy rate (mean) |

7 | 2.3 ± 0.08 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| Flares during pregnancy (%) |

38 | 28.6 ± 2.6 | 18 | |

| Flare-up postpartum (%) |

24 | 11.9 ± 2.0 | ||

| Total flares (%) | 39 | 36.5 ± 3.3 | ||

| IUGR (%) | 20 | 14.8 ± 0.8 | ||

| Preg-induced HTN (%) |

17 | 15.9 ± 2.7 | 19.3* | 17.2* |

| Gestational DM (%) |

8 | 6.7 ± 1.6 | 7.2 | 5.4 |

| APL ab (%) | 13 | 36.8 ± 6.1 | ||

| Neonatal lupus (%) | 25 | 2.4 ± 0.6 |

Elective termination= termination for personal or medical reasons

Fetal wastage= sum of miscarriages or spontaneous abortions and stillborn

IUGR= Intrauterine growth restriction

Pregnancy rate= number of pregnancies per woman

Preg-induced HTN = pregnancy-induced hypertension

Gestational DM= gestational diabetes

APL ab= antiphospholipid antibodies

* Sum of pregnancy-induced hypertension and toxemia

N= number of publications.

Literature Summary: SLE Peripartum Flares and Pregnancy Outcomes Presented in Mean % ± SEM and Median % with Interquartile Range (IQR) for Each Time Period

| N | Mean ± SEM % | Median ± IQR % | p-Value Between Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Flares during pregnancy |

<1990 | 13 | 25.9 ± 2.9 | 25.0 ± 10.4 |

0.002 |

| 1991-1998 | 11 | 41.8 ± 4.8 | 44.4 ± 25.6 | ||

| >1999 | 14 | 20.7 ± 4.0 | 16.0 ± 9.1 | ||

|

Flare-up postpartum |

<1990 | 8 | 16.3 ± 4.0 | 15.0 ± 22.3 |

NS |

| 1991-1998 | 8 | 13.3 ± 3.4 | 11.8 ± 16.23 | ||

| >1999 | 8 | 6.3 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 10.1 | ||

|

Total flares |

<1990 | 13 | 35.9 ± 5.0 | 34.0 ± 27.2 |

0.002 |

| 1991-1998 | 12 | 51.4 ± 6.0 | 52.5 ± 31.1 | ||

| >1999 | 14 | 24.3 ± 4.1 | 20.5 ± 20.0 | ||

|

Elective termination |

<1990 | 13 | 15.3 ± 2.5 | 15.6 ± 13.4 |

NS |

| 1991-1998 | 14 | 9.7 ± 2.5 | 7.9 ± 10.7 | ||

| >1999 | 17 | 7.5 ± 2.5 | 6.7 ± 9.1 | ||

|

Fetal wastage |

<1990 | 15 | 23.0 ± 3.5 | 17.9 ± 30.0 |

NS |

| 1991-1998 | 13 | 18.9 ± 2.5 | 19.4 ± 15.5 | ||

| >1999 | 17 | 16.8 ± 2.1 | 17.0 ± 15.1 | ||

|

Prematurity |

<1990 | 11 | 19.1 ± 4.4 | 12.5 ± 25.3 |

NS |

| 1991-1998 | 15 | 31.4 ± 3.5 | 27.0 ± 25.7 | ||

| >1999 | 17 | 24.5 ± 3.2 | 21.0 ± 17.7 | ||

|

Full term birth |

<1990 | 12 | 50.4 ± 5.7 | 57.5 ± 35.6 |

NS |

| 1991-1998 | 15 | 43.3 ± 3.2 | 42.6 ± 25.6 | ||

| >1999 | 17 | 52.9 ± 4.1 | 53.3 ± 25.7 | ||

|

Live birth |

<1990 | 16 | 64.9 ± 3.7 | 65.2 ± 23.6 |

0.024 |

| 1991-1998 | 16 | 74.5 ± 2.7 | 75.5 ± 21.3 | ||

| >1999 | 18 | 77.0 ± 3.1 | 78.2 ± 20.8 |

N= number of publications, NS=non-significant.

Eighty-three patients (77%) in the SLE group (N=108) had at least one pregnancy vs 93 (69%) in the control group (N=134). Sixty-seven (> 60%) SLE patients were pregnant prior to SLE diagnosis. Twenty-six of 83 SLE-women (31%) had at least one miscarriage. Pregnancy was associated with a self-reported SLE flare in 18% of patients; however, 18% of patients also reported improvement. The number of pregnancies per woman was similar between the groups (2.3 ± 0.2 for SLE and 1.8 ± 0.1 for controls; p = 0.17). SLE patients and controls had a similar age of first pregnancy. Twenty-four percent of lupus patients had at least one preterm delivery vs 5% in controls (OR = 8.32, p = 0.0008), but the pregnancy outcome was otherwise comparable (such as miscarriages, perinatal mortality). Thyroid problems (mainly hypothyroidism) were reported more in lupus patients (21% vs 10%, p = 0.02), but the frequency of other co-morbidities was similar to controls, such as hypertension (13% vs 21%, p = 0.1) and diabetes mellitus (2% vs 4%, p = 0.27). SLE patients were more likely to smoke during pregnancy (42% vs 24%, OR = 2.35, p = 0.009). Gynecological history including age at menarche and menopause, and frequency of irregular periods did not differ between the groups. SLE patients reported a shorter duration of oral contraceptive (OCP) use, and no difference in postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy use as compared to controls.

When adjusted for age, data were not different from those presented in Table 1, except age at menopause (p = 0.02). Also, SLE women were less likely to use any contraception (11% vs 4%, p = 0.03) and used OCP in similar numbers but for a shorter duration (56 vs 72 months, p = 0.0001). When adjusting for smoking on preterm birth, the relationships reported did not substantially change.

Our SLE cohort was primarily Caucasian, English speaking and fairly healthy. Ninety-five percent of our population was women, the mean age was 49.1 ± SEM 1.3 years and the mean disease duration was 11.4 ± SEM 1.3 years. The mean ± SEM SLAM [5], SLICC [6] and SLEDAI [7] scores were, respectively, 8.5 ± 0.3, 1.3 ± 0.4 and 6.7 ± 0.4.

We assessed laboratory data from 36 patients in our SLE population: 92% had positive ANA, 56% were positive for anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and 21% had antiphospholipid antibodies.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

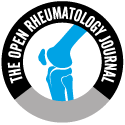

In total, 54 articles on lupus pregnancy published from 1963 to 2006 were reviewed [8-1]. Table 2 presents the results from the previously published studies compared to our present case-control study findings. Most of the results were similar between groups; however, we found that SLE flares (by self report) during pregnancy were less frequent in our population compared to the literature. Also, fewer patients from our study had prematurity or elective termination. Figs. (1,2) show results in median (%) for pregnancy outcome and SLE peripartum flares subdivided into 3 periods of publication date. Each time frame contains data from 18 publications. We noticed that over time, the rate of SLE peripartum flares has improved (p = 0.002), elective abortions (including termination for medical or personal reasons) have decreased, and the proportion of pregnancies resulting in live birth has increased (p = 0.024). The frequency of fetal death (the sum of spontaneous abortions or miscarriage and stillbirths) has not significantly changed. Results in mean (%) and median (%) were similar (Table 3).

|

Fig. (1). The frequency of SLE peripartum flares in the literature prior to 1990 vs most recent data. |

|

Fig. (2). The frequency of SLE pregnancy outcomes in the literature prior to 1990 vs most recent data. |

FERTILITY RATE

Fertility is defined as the ability to become pregnant. Seven publications [12, 33, 35, 37-38, 45, 59] demonstrated that the fertility rate in SLE is usually unaffected and comparable to the general population. Pregnancy rate (number of pregnancies per patient) varied from 2.0 to 2.6 (mean 2.3 ± SEM 0.08) (Table 2). However, certain factors predispose some SLE women to lower fertility. Severe renal failure and use of high doses of steroids might lead to menstrual irregularities or even amenorrhea [62]. In addition, previous treatment with alkylating agents can lead to ovarian failure [63]. Cyclophosphamide-induced premature ovarian failure is well documented. In fact, the incidence of ovarian failure is related to the age when starting cyclophosphamide, the duration of use and the cumulative dose [64-69]. In a retrospective series of 39 SLE patients who had received intermittent pulses of cyclophosphamide therapy, Boumpas et al. reported that sustained amenorrhea occurred in 12% of patients < 25 year of age, in 27% of patients between 26 to 30 years old and in 62% of patients older than 31years [64]. In a study of 67 SLE premenopausal women who were treated with monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide, 31% developed sustained amenorrhea of at least 12 months. In this same study, the cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide resulting in sustained amenorrhea in 50% and 90% of the women (D50 and D90) was 8 g/m2 and 12 g/m2, respectively [68].

In order to preserve fertility and to minimize cyclophosphamide gonadotoxicity, an adjuvant treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonistic analogue (GhRH-a) may be an option [70-71], although this is not widely adopted. Some clinics use oral contraceptive pills to prevent ovulation as theoretically having less risk to an anovulatory ovary. There are trials of exogenous estrogen and lupus flare, and both contraceptive hormones and post menopausal hormones in RCTs seem to be relatively safe. There are some contraindications for hormone use in young women with lupus such as known hypercoaguable state, and some relative contraindications such as migraines, hypertension and smoking [72, 73].

PREGNANCY OUTCOME

Various publications have reported an increased incidence of prematurity, fetal death (the sum of spontaneous abortions or miscarriage and stillbirths) and intrauterine grown retardation (IUGR) in SLE. Dhar et al. reviewed 16 studies on pregnancy outcomes before and after the diagnosis of SLE [74] and found that, in spite of some limitations in study design and statistical analysis and variations in terminology used, most studies concluded that pregnancy loss [8, 21, 31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 48, 50, 56, 51, 70, 71,74], preterm births [8, 21, 31, 34, 38, 48, 49, 51, 74 and IUGR [8, 31, 33, 34] were more common after than before the diagnosis of SLE and compared to a control population.

From our review of 45 studies [9-15, 17-30, 32-34, 36, 39, 40, 42, 45-61], the frequency of fetal death varied from 4% to 43% (mean 19.5% ± SEM 1.6%) (Table 2), which is higher than in the general population [21, 31, 32, 35, 37]. In another study, the authors reported a 4-fold increase in the risk of stillbirth in lupus patients. They also found that the risk was halved if they excluded patients with central nervous system (CNS) disease [74]. Further investigation is needed to confirm this correlation in lupus pregnancy. Several factors may predict fetal death such as lupus disease activity, active lupus nephritis [22], and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.

Fetal prognosis depends mostly on disease activity, with fetal loss ranging from 25-52% in patients with active SLE compared to 8-12% in patients with inactive SLE at the onset of pregnancy. The latter rate is comparable to observations in healthy women [17-21].

Active renal disease has been associated with 8-24% of fetal loss from miscarriages [23] and 4-24% of stillbirths and neonatal deaths [17, 19, 22-25]. Thus, active lupus nephritis patients are often advised to avoid pregnancy. However, during inactive SLE, the pregnancy outcome is usually favorable [17, 19]. Rahman et al. reported on a series of 141 SLE pregnancies where maternal active renal disease was present in 33% of pregnancies resulting in fetal loss vs 13% of pregnancies with live births (p < 0.012) [22]. In SLE patients a history of nephritis, maternal hypertension (OR 6.4), proteinuria > 0.5g/day (OR 13.3) and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (OR 17.8) have been shown to be predictive of adverse fetal outcome [20]. Another report from Hong Kong analyzed a subgroup of 27 patients with a past history of lupus nephritis; they found that significant proteinuria (p = 0.01) and active disease (p = 0.03) at conception and during the gestation were predictive of poor fetal outcome [75].

Antiphospholipid antibodies are present in 36.8% ± SEM 6.1% of SLE patients in 13 publications [15, 16, 19-21, 26-28, 47, 49, 52, 60, 61] (Table 2). The association between these antibodies and fetal loss has been well demonstrated [10, 23]. Mok et al. studied 91 pregnancies, reporting that antiphospholipid antibodies were more prevalent in patients with recurrent miscarriages (p = 0.008, OR = 14.3) and the strongest predictive factor was the presence of lupus anticoagulant (p = 0.002, OR 23.3) [75]. Mechanisms could include lack of implantation, placental vasoconstriction and thrombosis leading to either fetal growth restriction or death [23, 76]. The literature indicates that the presence of these antibodies is associated with an approximately 2-fold increase in fetal loss (as high as 30-83% of pregnancies compared to a 4-43% fetal loss rate in antiphospholipid antibody negative SLE patients) [20, 23, 51, 77-78]. Fetal outcome is significantly improved with the use of heparin and low dose aspirin in these cases [79-80]. A recent review by Erkan et al. summarized the current evidence on the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy [81].

Lupus is associated with an increased rate of prematurity. Preterm delivery frequency in the general population varies between 4% and 9% [9, 23, 30, 35, 42]. Our analysis of 43 studies found a mean of 25.5% ± SEM 2.2%, with a range of 4% to 62% [8-16, 17-25, 27-29, 30-34, 38-40, 42-43, 46-49, 51-60] (Table 2). The discrepancies in the literature in terms of frequency of prematurity in SLE might be due to differences in definitions of prematurity, the rate of therapeutic or spontaneous abortions and the fact that preterm birth in SLE has multiple causes. Reasons for prematurity seem to be SLE activity [9-10, 15, 32, 47, 52, 55, 75], maternal hypertension [15, 21, 22, 32, 82], history of fetal loss [15], pre-eclampsia [19], antiphospholipid antibodies [9-10, 30], placental insufficiency and an increased prevalence of premature rupture of the membranes [28, 83].

Several studies mentioned that corticosteroid use during pregnancy increased the risk of preterm birth [9, 10, 15, 47, 50, 55]. Indeed, a retrospective study demonstrated a correlation between the use of > 10mg/day of prednisone in SLE pregnant women and an increased rate of preterm births [9]. However, this could be confounded by SLE disease activity. A study from Japan showed the frequency of preterm delivery in patients receiving > 15mg/day of prednisone was 60% vs 13% in patients who received 0-15mg/day (p < 0.05) [55]. However, a higher dosage of corticosteroid is often necessary to control disease activity, which may also contribute to premature delivery. In addition, corticosteroids may impair the placental function and induce premature rupture of membranes.

Three randomized trials have evaluated the usefulness of corticosteroids in pregnant women with unexplained or antiphospholipid antibody-associated fetal loss. All concluded that corticosteroids did not improve fetal outcome. On the contrary, the treatment group had a significantly increased rate of preterm births and maternal morbidities or obstetrical complications such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia and premature rupture of the membranes [44, 84-86].

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) occurs in 14.8% ± 2.0% of SLE pregnancies in 20 studies [8, 10, 11, 15, 19, 22, 26, 27, 30-32, 39, 42, 47, 53, 57-61]. The main factors contributing to the increased rate of growth restriction are hypertension [15, 22], corticosteroids, antiphospholipid antibodies [10, 76] and pre-eclampsia [19, 22, 36, 83, 87]. Low complement levels also seem to correlate with IUGR [15, 55].

LUPUS FLARES

Diagnosis of a lupus flare in pregnancy may be difficult; normal physiological changes or pregnancy related complications such as pre-eclampsia can mimic a lupus flare. The effect of pregnancy on SLE activity has received much attention; however, the exact consequence of pregnancy on the course of SLE is not conclusively determined. Some authors have reported an increased frequency of flares [42-44], but others have found a rate similar to a non-pregnant SLE population [40-41]. Differences in the definitions of lupus flare, as well as patient or control group characteristics might contribute to these contradictory results. Overall, we found that lupus flares are common in pregnancy: our analysis of 39 publications showed a mean rate of lupus reactivation of 36.5% ± 3.3% (Table 2) [10, 11, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 22, 25, 28, 32-35, 30, 42-44, 49, 53-56, 59-61].

Some factors might increase the risk of flares. Most studies agreed that flares occurred more often in SLE patients with active disease at conception [17, 18, 54-56, 59]. A publication from Japan noted the frequency of SLE flares was 13% in inactive patients at conception vs 75% in patients with active disease [55]. Moroni et al. reported fetal and maternal outcomes of 51 pregnancies in women with a history of lupus nephritis. They demonstrated that the only predictor of renal flare was the presence of any sign of renal disease activity at the onset of pregnancy. Indeed, renal flares occurred in 5% of patients with quiescent renal disease compared to 39% in patients with active renal disease (p = 0.01) [20]. In addition, the literature has shown that flares might occur in any trimester or during the post-partum period [32, 42-44]. Usually, the severity of the flare is mild with arthritis, constitutional and cutaneous manifestations being common [5, 43]. However, more serious problems affecting the kidneys and central nervous system have been reported in 46% and 14% of patients, respectively [32, 42-43]. Therefore, close monitoring and multidisciplinary care are essential during the pregnancy and post-partum period.

Serum prolactin normally rises early in pregnancy and persists at a high level through the breast-feeding period. Several publications have attempted to establish a relationship between hyperprolactinemia and lupus disease activity, but results have been contradictory [88-95]. To our knowledge, only one case report has been published on breast-feeding and lupus reactivation postpartum [96]. Actually, there is no evidence of postpartum SLE exacerbation by breast-feeding.

DISCUSSION

The findings from our case-control study were compared to those from the literature. We found no statistical difference between the SLE vs control group for fertility rate, gynecological history and pregnancy outcome except for prematurity (Table 1). More SLE women had preterm delivery compared to the control population. When we adjusted for possible confounding variables for each pregnancy outcome, we obtained a lower frequency of preterm birth and elective termination (Table 2). Also, lupus flares in our cohort during the course of pregnancy were lower than reported from the literature. Differences might be related to the characteristics of our study population, as age, ethnicity, disease status, treatment and personal information (such as occupation, education and living conditions) can influence clinic outcomes significantly.

The diagnosis of SLE was confirmed for cases in our study but obstetrical chart review was not done. However, we presume the data are reliable as most women recall their reproductive history accurately and it is unlikely that recall bias will have a significant influence on the accuracy of results. Also, our results were generally consistent with the current literature.

We found that SLE subjects were more likely than controls to have thyroid problems (Table 1), and thyroid disease is known to be more common in SLE [97-99]. We did not assess the temporal relationship between thyroid disease and SLE pregnancy, as the timing of thyroid disease onset and pregnancies was not determined. A limitation could be that many of our patients had their pregnancies prior to being diagnosed with SLE.

Other co-morbidities were similar with the exception of smoking during pregnancy, which was higher in SLE women. Education (such as counseling about conception to be planned while the lupus is inactive for a better outcome for mother and baby) and close monitoring of pregnant patients may positively impact on the outcome. Although we did not find smoking as a risk in our population for adverse pregnancy outcome, it is obvious that smoking cessation should be encouraged in those contemplating pregnancy and during pregnancy. This study was likely underpowered to demonstrate ill effects of smoking in lupus such as small-for-dates babies.

From the 54 published papers we reviewed altogether, in spite of some differences in the study populations, design, and definitions used for pregnancy outcomes or lupus reactivation, we assessed in total 3740 SLE pregnancies. The literature showed an improvement in fetal and maternal outcome since the last decade (Figs. 1, 2 and Table 3). Moroni et al. retrospectively analyzed fetal and maternal outcomes in SLE patients with lupus nephritis, noting that fetal loss has decreased from 46% to 30% since the 1970s [20]. Furthermore, treatment with heparin of patients who have antiphospholipid antibodies began in 1989. A higher rate of live birth (71% vs 30%) (p = 0.0013) was observed by Cortés-Hernández et al. since the induction of this new therapy in these patients [10]. Obviously, important progress made in maternal disease control and improvements in obstetrical care have contributed to better fetal outcomes.

The are several other possible reasons that pregnancy outcomes may be improving over time including: less severe SLE over time; more mild patients being diagnosed; conception counseling about timing of pregnancy when SLE is inactive; better multidisciplinary care; increased contraception use in ill patients; and a trend for better pregnancy outcome for all women in the general population.

CONCLUSIONS

This article summarizes much of the information available on pregnancy outcomes in SLE and adds data from our cohort of women with SLE. Fertility is not affected in SLE patients; however, despite recent progress in obstetrical care, maternal and fetal complications still exist. Pregnancy in SLE patients should be considered as a high-risk pregnancy and conception should be planned, if possible, during a quiescent period. Close monitoring for optimal disease control and multidisciplinary obstetrical care are necessary throughout the gestation period to increase the chances of a successful pregnancy.