All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Medication-related Self-management Behaviors among Arthritis Patients: Does Attentional Coping Style Matter?

Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between the attentional coping styles (monitoring and blunting) of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) patients and: (a) receipt of medication information; (b) receipt of conflicting medication information; (c) ambiguity aversion; (d) medication-related discussions with doctors and spouse/partners; and (e) medication adherence.

Method:

A sample of 328 adults with a self-reported diagnosis of arthritis (RA n=159; OA n=149) completed an Internet-based survey. Coping style was assessed using the validated short version of the Miller Behavioral Style Scale. Measures related to aspects of medication information receipt and discussion and validated measures of ambiguity aversion and medication adherence (Vasculitis Self-Management Survey) were collected. Pearson correlation coefficients, ANOVA, independent samples t-tests and multiple regression models were used to assess associations between coping style and the other variables of interest.

Results:

Arthritis patients in our sample were more likely to be high monitors (50%) than high blunters (36%). Among RA patients, increased information-receipt was significantly associated with decreased monitoring (b = -1.06, p = .001). Among OA patients, increased information-receipt was significantly associated with increased blunting (b = .60, p = .02).

Conclusion:

In our sample of patients with arthritis, attentional coping style is not in accordance with the characteristic patterns outlined in the acute and chronic disease coping literature.

INTRODUCTION

Unlike some chronic diseases which may have an acute onset such as multiple sclerosis (MS), an important feature of arthritis is its progressive, unpredictable and insidious nature [1]. There is no cure for arthritis, and patients are often faced with a range of stressors such as adjusting to fluctuations in symptoms (e.g., joint pain and restricted movement) and treatment (e.g., medication changes) [2, 3]. Arthritis requires sufficient patient knowledge about the condition and an ability to perform self-management activities (also described in the literature as coping strategies) [4] such as taking medication and accessing information [5]. Coping strategies also may influence how arthritis patients attend to treatment related information and how well they adhere to their medication regimen [6-8]. Additionally, coping behaviors may be influenced by differences in arthritis type. For example, while many symptoms of osteoarthritis (OA) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) overlap (e.g., pain, swelling, and joint stiffness) their etiology, course, and treatment differ. RA is generally considered more disabling and its management more intensive compared to OA, which tends to be slowly progressive and generally occurs later in life [9, 10]. Further, OA is often treated with drugs that alleviate symptoms but do not change the disease course, such as acetaminophen, while disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (e.g., methotrexate) or biological therapies (e.g., adalimumab) are often used to treat RA.

Research in disease self-management and coping seems to parallel the shift towards patients being more actively involved in their health care. Patients are likely to use different strategies as they adapt to different stages of the chronic disease process [11], however, stress-coping theory posits that general coping styles influence the strategies patients use across specific situations and time [11-13]. Two distinct styles that have received considerable attention reflect a preference to either orient one’s attention toward or away from the health condition [14]. The evaluation of a patients’ general tendencies to either seek or avoid potentially stressful information, has been referred to as “monitoring” and “blunting,” respectively [14]. While previous studies have considered these constructs unidimensionally, newer scrutiny indicates they should be considered separately [15].

Many studies have assessed attentional coping style in a variety of acute health contexts (e.g., cardiac catheterization, endoscopy, cancer screening, chemotherapy treatment) and findings tend to be consistent: monitors cognitively and behaviorally attend to information (e.g., search for side effect information online and talk about the stressor with other people) and do better with and prefer more information, while blunters tend to avoid information (e.g., talk about things unrelated to their medical condition) when confronted with medical stressors and do better with and prefer less information [15-19]. A review of distressful situations related to cancer (i.e., screening) found high monitors to be more compliant with medical recommendations compared to low monitors [19]. There also is evidence showing that aversion to ambiguous health information related to prevention advice lowers adherence to health recommendations [20] and that monitors become distressed by ambiguous, threatening, negative health information, whereas blunters respond less sensitively [19].

Few studies have explored attentional coping orientation related to self-management behaviors in people with chronic diseases where stress is present but not always acute. In a review of coping strategies used by asthma patients, blunting strategies (e.g., denial) were commonly used by patients with poor medication adherence [21]. One study, concentrating on coping style and information-seeking behavior among people with MS, found that monitors were more interested in information about MS and preferred information earlier in the disease process than did blunters [22]. One study of individuals with chronic pain found that tailoring a pain management intervention to the preferred monitor or blunter coping strategy reduced anxiety levels [23].

We are not aware of any studies that have considered whether arthritis patients’ expressed coping style is consistent with self-management behaviors related to medication information and more distal outcomes of care such as medication adherence. Arthritis specific studies have found coping style to have a strong association with response and adjustment to arthritis: avoidant coping strategies generally tend to be associated with negative health outcomes (e.g., more disability and poorer psychological health); whereas, monitoring strategies tend to be associated with more positive outcomes [7, 8, 24-26]. However, one study of 77 rheumatoid arthritis patients found that high monitoring, compared to low monitoring, was associated with psychological distress when patients struggled with uncertainty [27].

This study investigates the relationship between RA and OA patients’ attentional coping styles and behaviors related to medication information (i.e., receipt of information from various sources, receipt of conflicting information, ambiguity aversion, medication-related discussions with providers and spouses) and medication adherence. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that patients with higher monitoring would receive more medication information, receive more conflicting medication information, report greater ambiguity aversion, and have more frequent medication related discussions with doctors and spouse/partners compared to patients with lower monitoring. We further hypothesized that, patients with higher blunting or lower monitoring would report poorer medication adherence compared to lower-blunting or higher-monitoring patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

Subjects

All data were collected as part of the Information Networks for Osteoarthritis Resources and Medications (INFORM) study, which included a cross-sectional, 30-45 minute on-line survey that assessed the self-reported health behaviors and health status of arthritis patients. Eligible participants had a self-reported doctor-diagnosis of arthritis, were currently taking at least one medication to treat their arthritis on a routine basis, were at least 18 years of age, could read and write in English, and had Internet access. Medicine taken only occasionally (infrequently) and creams were not considered routine medicines. All participants agreed to participate after reading a study fact sheet and received a $10 incentive for participating. The INFORM study was approved by the University of North Carolina’s Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki..

Recruitment methods have been described in detail elsewhere [28]. Briefly, recruitment mailings were sent to persons having a diagnosis of osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis according to University of North Carolina Hospital System records and general recruitment announcements were distributed via patient websites, local clinics, arthritis support groups, and in local media publications and advertising outlets. A total of 424 patients accessed the study survey between May 2010 and January 2011. Among those, 71 individuals were ineligible (34 did not meet eligibility criteria; 7 were missing screeners; 30 surveys were incomplete or duplicate); and, 25 declined to participate after reading the fact sheet. Three hundred twenty eight patients completed the study survey; 124 were recruited from the hospital mailing and 204 from general announcements. We were unable to calculate response rate because the number of arthritis patients who were exposed to the general announcements and advertisements was not known.

Measures

Miller Behavioral Style Scale

The abbreviated Miller Behavioral Style Scale (MBSS) was used to measure levels of attentional coping style for each study participant [29]. It consists of two stress-evoking scenarios (dentistry and job-loss) in which patients are asked to mark whether eight statements apply to how they would cope with the scenario. Responses to the abbreviated MBSS are scored as 1 (yes) or 0 (no). Each monitoring (4 items in each scenario) and blunting (4 items in each scenario) response is then summed across both scenarios to produce a monitoring (higher score equals more monitoring) and blunting (higher score equals more blunting) subscale score (range: 0-8 for each subscale) [14]. Monitoring and blunting subscales are considered separately rather than as a summary score of both, because the two subscales have been found to reflect independent constructs [15], and the correlation between the monitoring and blunting subscale scores in this study was very weak (r =.10). The abbreviated version of the MBSS has been validated in samples of patients with chronic disease [30, 31].

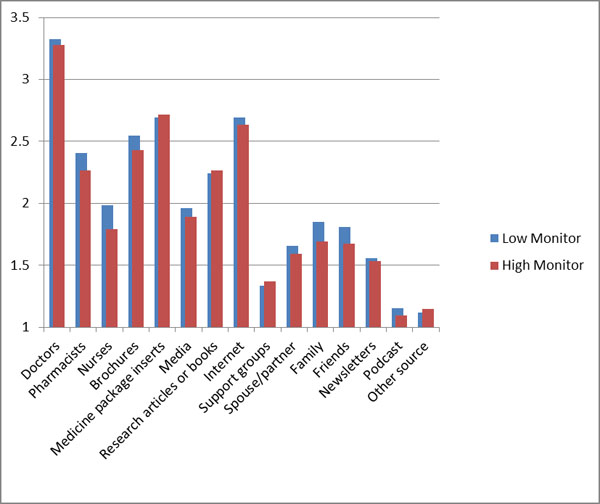

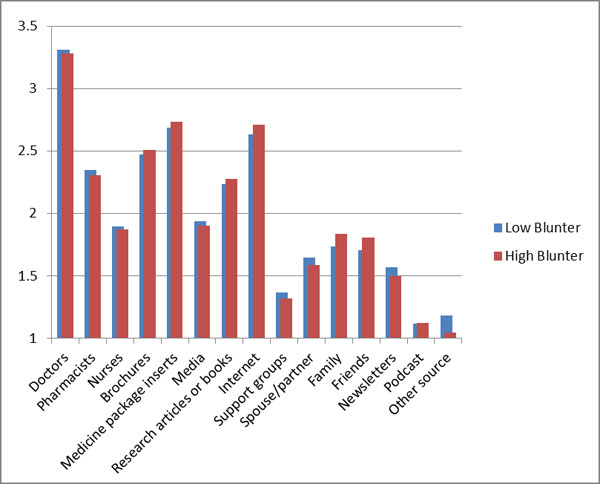

Medication Information Received from Various Sources

Patients were asked how much medicine information they receive (either solicited or unsolicited) when they begin taking a new arthritis medicine from the following fifteen different information sources: physicians, pharmacists, nurses, brochures and pamphlets, medicine package inserts, articles and books, newsletters, Internet (information websites), support groups (online or in-person), spouse/partner, family members other than their spouse, friends, media sources, commercials or advertisements, and podcasts (Cronbach's alpha = .83). For each source, patients answered one item about how much medicine information they receive, ranging from 1= “none” to 4= “a lot.” Patients’ responses were averaged and higher mean scores correspond to obtaining greater amounts of medication information across sources. A simple count of the total number of sources was also calculated, with a higher number corresponding to greater number of sources from which patients obtained any medication-related information.

Conflicting Medication Information

Patients were asked 12 questions related to how often they received conflicting information about specific medicine topics from two or more different sources (e.g., a doctor and the Internet, the Internet and the medicine package insert) (Cronbach's alpha = .91). Examples of medicine related topics include the following: what time of day to take arthritis medicines and the side effects associated with arthritis medicines. Scale item responses ranged from: 1 = “never received” to 4 = “often received.” Patients’ responses were averaged with higher scores representing more receipt of conflicting information.

Ambiguity Aversion

The six item Ambiguity Aversion Med Scale (AA-Med scale) is used to assess aversion to ambiguity regarding medical tests and treatments [32]. Adapted items assess aversion to ambiguity regarding arthritis medicines in 3 content domains (i.e., cognitive (“Conflicting expert opinions about taking a medicine would lower my trust in the experts”); affective (“Conflicting expert opinions about taking a medicine would make me upset”); and, behavioral (“I would avoid making a decision about taking a medicine if experts had conflicting opinions about the medicine.”). All items used a 5-point response scale numbered from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items were averaged and higher scores represent greater levels of ambiguity aversion (Cronbach’s alpha = .77).

Medication Discussions with Provider and Spouse

Patients were asked how often they discussed eight medication information related topics with the doctor who writes their arthritis prescriptions. Topics included: medication in general, how to take medicines, medication side effects, drug interactions, costs, complementary and alternative medicines, trials, and medication effectiveness in treating symptoms (Cronbach's alpha = .90). All items used a 4-point response scale numbered from 1 “we never discuss” to 4 “we discuss a lot.” Items were averaged and higher scores represent more frequent arthritis medicine discussions with their doctor. The same procedure was used to assess how often patients discussed the same eight medication information related topics with their spouse/partner (Cronbach's alpha = .90).

Medication Non-adherence

To measure medication non-adherence, we used one item from the standardized and validated Vasculitis Self-Management Survey (VSMS) (percentage of medication doses taken exactly as directed (prescribed and/or recommended by the patient’s doctor)) (responses included:1=0-24%, 2=25-49%, 3=50-74%, 4=75-99% and 5=100% [33]. The VSMS asks respondents to describe their medication-taking behavior during the past 4 weeks. Lower scores indicated poorer adherence for all medications the patient was taking to treat their arthritis.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Patients reported their age, gender (male, female), race/ethnicity (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, Other), and education level (i.e., 8th grade or less, some high school but no diploma, high school graduate or GED, some college but no degree, associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, postgraduate school or degree; assigned as the total number of years of education (8,9,12,13,14,16,18). Patients reported their year of arthritis diagnosis and doctor-diagnosed arthritis type (osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis). Arthritis severity was assessed using one item (“Based on how you have been feeling during the past 4 weeks, please select the one number that best represents how severe you consider your arthritis to be.”); responses included:1 = not at all severe; 5 = moderately severe; and 10 = extremely severe. According to their treatment plan, patients listed the names of the medications taken routinely to treat their arthritis, which was dichotomized into medication type with 1= patient listed DMARD/biologic agent and 2= patient did not list a DMARD/biologic agent.

Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, means and standard deviations for continuous variables) were used to summarize sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants. The differences in mean scores for monitoring and blunting coping style among various sociodemographic and clinical characteristics/groups were analyzed by ANOVA and/or t-tests. Tukey’s studentized range test was used to adjust for multiple comparisons among different levels of the explanatory variables. By arthritis type, considering monitoring and blunting separately, Pearson correlation coefficients and independent samples t-tests were used, as appropriate, to examine bivariate relationships between the continuous coping style scores and the following measures: medication information receipt, receipt of conflicting medication information, ambiguity aversion, discussing aspects of medicines with doctor or spouse/partner and medication non-adherence (alpha = .05). Lastly, multiple regression analyses were conducted for RA and OA patients separately, using backward elimination, in order to determine the effects of potential confounders on coping style (monitoring vs. blunting). Variables evaluated for inclusion in the adjusted regression model were: age, gender, number of years of education, arthritis duration, arthritis severity, arthritis type, medication information receipt, receipt of conflicting information, ambiguity aversion, discussion with doctor, discussion with partner, and medication adherence. P values of less than or equal to .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients were more likely to be high-monitors (50%) compared to high-blunters (36%). Means and standard deviations for monitor and blunter coping style by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2. Specific types of info sources most frequently utilized by each coping style group (monitor and blunter) are presented in Figs. (1a and b).

| N | (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 68 | 21 | |||

| Female | 260 | 79 | |||

| Race | |||||

| White | 262 | 80 | |||

| African American | 45 | 14 | |||

| Othera | 21 | 6 | |||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 18-44 years | 50 | 15 | |||

| 45-64 years | 192 | 59 | |||

| ≥65 years | 86 | 26 | |||

| Education levelb | |||||

| ≤High school diploma | 50 | 15 | |||

| At least some college | 114 | 35 | |||

| Completed college or greater | 164 | 50 | |||

| Arthritis typeb | |||||

| Osteoarthritis | 149 | 48 | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 159 | 52 | |||

| Medication typeb | |||||

| DMARD/biologic agent | 219 | 67 | |||

| No DMARD/biologic agent | 106 | 33 | |||

| Medication adherenceb | |||||

| Medication taken ≤74% as directed | 51 | 16 | |||

| Medication taken ≥75% as directed | 272 | 84 | |||

| Arthritis duration (years)b | |||||

| <5 years | 99 | 32 | |||

| 6-20 years | 158 | 51 | |||

| > 20 years | 53 | 17 | |||

| Miller Behavioural Style (Monitor) † | |||||

| High | 163 | 50 | |||

| Low | 165 | 50 | |||

| Miller Behavioural Style (Blunter) † | |||||

| High | 118 | 36 | |||

| Low | 210 | 64 | |||

Correlates of Attentional Coping Style

Table 3 provides correlation matrices (i.e., RA patients only and OA patients only) and significance values for coping style, factors related to medication-related information and medication non-adherence.

|

Monitor M (SD) |

Blunter M (SD) |

|

|

Gender Male Female |

3.26 (2.12) 3.63 (1.82) |

1.95 (1.33) 2.27 (1.48) |

|

Race White African American Other |

3.66 (1.91) 2.88 (1.66) 3.66 (1.85) |

2.19 (1.43 2.24 (1.55) 2.33 (1.59) |

|

Age Group (years) 18-44 years 45-64 years ≥65 years |

4.08 (2.30)* 3.43 (1.80) 3.54 (1.79) |

2.06 (1.33) 2.29 (1.54) 2.10 (1.32) |

|

Education levelb ≤High school diploma At least some college Completed college or greater |

3.04 (1.94) 3.26 (1.71) 3.92 (1.92) |

2.22 (1.35) 2.22 (1.40) 2.19 (1.53) |

|

Arthritis Typeb Osteoarthritis Rheumatoid Arthritis |

3.49 (1.88) 3.74 (1.89) |

2.36 (1.50) 2.10 (1.41) |

|

Medication Typeb DMARD/biologic agent No DMARD/biologic agent |

3.92 (1.79) 3.44 (1.89) |

2.12 (1.45) 2.28 (1.45) |

|

Medication adherence Medication taken ≤74% as directed Medication taken ≥75% as directed |

3.67 (2.03) 3.61 (1.82) |

2.18 (1.29) 2.25 (1.48) |

|

Arthritis Duration (years) b <5 years 6-20 years > 20 years |

3.50 (1.89) 3.52 (1.86) 3.60 (2.04) |

2.11 (1.42) 2.37 (1.54) 1.84 (1.19) |

| RA patient data (n=159) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor | Blunter | CMIreceipt | MIreceipt | AmbAver | MedAdh | DissDoc | DissPart | |

| Monitor | -0.006 | -0.223 | -0.303** | -0.086 | -0.108 | -0.079 | -0.052 | |

| Blunter | -0.006 | -0.025 | 0.024 | 0.062 | -0.008 | 0.068 | -0.109 | |

| CMIreceipt | -0.223 | -0.025 | 0.400** | 0.076 | -0.171* | 0.029 | 0.254* | |

| MIreceipt | -0.303** | 0.024 | 0.400** | 0.152 | 0.196 | 0.415** | 0.375** | |

| AmbAver | -0.086 | 0.062 | 0.076 | 0.152 | -0.082 | 0.056 | 0.167 | |

| MedAdh | -0.108 | -0.008 | -0.171* | 0.196 | -0.082 | 0.030 | 0.143 | |

| DissDoc | -0.079 | 0.068 | 0.029 | 0.415** | 0.056 | 0.030 | 0.419** | |

| DissPart | -0.052 | -0.109 | 0.254* | 0.375** | 0.167 | 0.143 | 0.419** | |

| OA patient data (n=149) | ||||||||

| Monitor | Blunter | CMIreceipt | MIreceipt | AmbAver | MedAdh | DissDoc | DissPart | |

| Monitor | 0.190* | 0.031 | -0.027 | -0.131 | -0.056 | -0.176* | -0.210* | |

| Blunter | 0.190* | 0.135 | 0.156 | -0.218* | 0.067 | 0.039 | 0.061 | |

| CMIreceipt | 0.031 | 0.135 | 0.229* | -0.089 | -0.171* | 0.144 | 0.054 | |

| MIreceipt | -0.027 | 0.156 | 0.229* | 0.040 | 0.162 | 0.436** | 0.464** | |

| AmbAver | -0.131 | -0.218* | -0.089 | 0.040 | -0.004 | 0.065 | 0.040 | |

| MedAdh | -0.056 | 0.067 | -0.171* | 0.162 | -0.004 | 0.151 | -0.041 | |

| DissDoc | -0.176* | 0.039 | 0.144 | 0.436** | 0.065 | 0.151 | 0.501** | |

| DissPart | -0.210* | 0.061 | 0.054 | 0.464** | 0.040 | -0.041 | 0.501** | |

Multiple Regression of Attentional Coping Style by Arthritis type

Among OA patients (n=149), female gender was significantly associated with increased monitoring (b = 1.03, p = .005). Controlling for the effect of gender, monitoring significantly increased with more years of education for OA patients (b= 0.14, p = .03). Among OA patients, blunting significantly decreased with disease duration (b= -0.03, p = .04). Controlling for disease duration, increased information-receipt was significantly associated with increased blunting among OA patients (b = .60, p = .02).

Among RA patients (n=159), monitoring significantly increased with more years of education (b= .21, p = .003). Controlling for years of education, increased information-receipt was significantly associated with decreased monitoring for RA patients (b = -1.06, p = .001). Among RA patients, no significant associations were found between age, gender, number of years of education, arthritis duration, arthritis severity, arthritis type, medication information receipt, receipt of conflicting information, ambiguity aversion, discussion with doctor, discussion with partner, medication adherence and blunting scores.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine whether arthritis patients’ expressed coping style is consistent with self-management behaviors such as how often patients have medication related discussions with their doctors and more distal outcomes of care such as medication adherence. In line with the prevailing view that monitoring and blunting are largely independent constructs, we observed a very weak association between the subscales. Arthritis patients in our sample were more likely to be high monitors than high blunters, which supports previous research showing that the prevalence of blunting coping style among individuals with chronic health problems is between 30%-50% [34].

In our sample of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, attentional coping style is not in accordance with the characteristic patterns outlined in the acute and chronic disease coping literature. Our hypotheses that higher monitoring would be associated with self-management behaviors related to medication information and that more blunting and less monitoring would be associated with medication non-adherence were not supported, even accounting for relevant demographic and clinical factors. We were surprised by the lack of findings given that the literature on acute health conditions has consistently reported attending to higher levels of health information and discussing health related information with others are common coping strategies for individuals with monitoring traits and that monitors perceive ambiguous information as threatening [15-19]. That higher monitors in our sample were not more likely to receive conflicting information was also surprising, given research shows the majority of arthritis patients have reported receiving conflicting medication-related information; one would expect more receipt of medication information, in general, would expose a higher monitor to more conflicting information [28]. That neither higher blunting nor lower monitoring was found to be associated with poorer medication adherence is not supported by data showing use of blunting strategies such as denial are associated with poor medication adherence [21] and higher monitoring is associated with more medical recommendation compliance [19].

Our finding that higher monitoring was related to less information-receipt for RA patients is also counter to previous findings in the chronic disease coping literature. Two previous studies with asthma and MS patients showed that monitoring was related to interest in gaining more information [21, 22] and another study of coronary heart disease patients found a preference for medication risk and side effect information to be associated with monitoring [35]. Also, counter to expected coping trends, we found that among OA patients, higher blunting was associated with more information-receipt. The MBSS was designed as a broad measure of monitoring and blunting across diverse situations [36]. The items are not specifically related to arthritis and may not be sensitive enough to detect attendance away from or toward arthritis-specific stressors such as changes in medication regimen. Also, arthritis patients, regardless of arthritis type, may find different aspects of coping with their disease more stress-provoking than others and not engage in expected monitoring and blunting strategies when they are prescribed a new medication. A possible explanation for the RA finding could be that adversity can cause excessive rumination or monitoring which can be maladaptive and can lead to a tendency away from engaging or focusing on tasks [37]. The unexpected RA and OA findings may also be a result of how information receipt was assessed. Monitors and blunters may differ in their perception of degrees of information receipt (e.g., “a lot”).

Findings related to specific patient demographic and clinical characteristics showed that for both OA and RA patients, increased monitoring was associated with more education. Being female was associated with increased monitoring and increased arthritis duration was associated with decreased blunting for OA patients. Results from other studies are mixed with some showing females [38] and individuals with higher education [38, 39] being more likely to orient their attention toward the health condition or to seek out health information, while other findings show no association with these demographic characteristics [40] or found males more likely to exhibit higher monitoring com-pared to females [41]. Two studies found no association between disease duration and blunting coping style [40, 42].

The use of cross-sectional design limits our ability to assert causal relationships between attentional coping style and medication-related behaviors. However, this study was designed to examine arthritis patient coping style and factors associated with receipt of medication-related information and medication adherence for a single-time point, which has not been done previously. Future longitudinal research should consider the stability of monitoring and blunting traits over time and the potential for a reverse-causal relationship (e.g., Does lower information receipt lead to greater monitoring?). It is possible that patients with severely disabling RA or OA, those with mild OA, those without internet access or computer literacy skills were underrepresented in our online survey sample, which impedes our ability to generalize the results to the greater population of arthritis patients. While this study was limited to self-management activities related to accessing information and taking medication, future studies should explore if these results are generalizable to other chronic health conditions. Further, some patients may have under-reported non-adherence and our use of a subjective self-report measure rather than objective measure of adherence, such as electronic monitoring, may not have been as reliable a measure of non-adherence. A review of the literature found that self-report of adherence provides a reasonably accurate assessment of adherence and that most participants who self-report non-adherence are non-adherent [43].

CONCLUSION

These findings are relevant to arthritis patients, clinicians who treat them, public health and mental health professionals concerned with relations among coping style and medication-related behavior. In our sample, coping style did not seem to affect medication-related behaviors for arthritis patients in a predictable way. More research is needed to better understand the long term relationship between coping style and patient medication-related behaviors in order to help clarify why and when health-relevant information is likely to benefit or harm arthritis patients. It may be useful to evaluate monitoring and blunting in terms of if and how the two components may work together to reduce stress in individuals with arthritis over time [44] and to qualitatively study the negative relationship between monitoring and information receipt and medication adherence. A more nuanced coping style measure for arthritis patients is needed to evaluate the association between attentional coping in various arthritis specific scenarios.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the TraCS Institute at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for assistance with recruitment, and Kristen Morella and Mark Weaver for their analytical support.